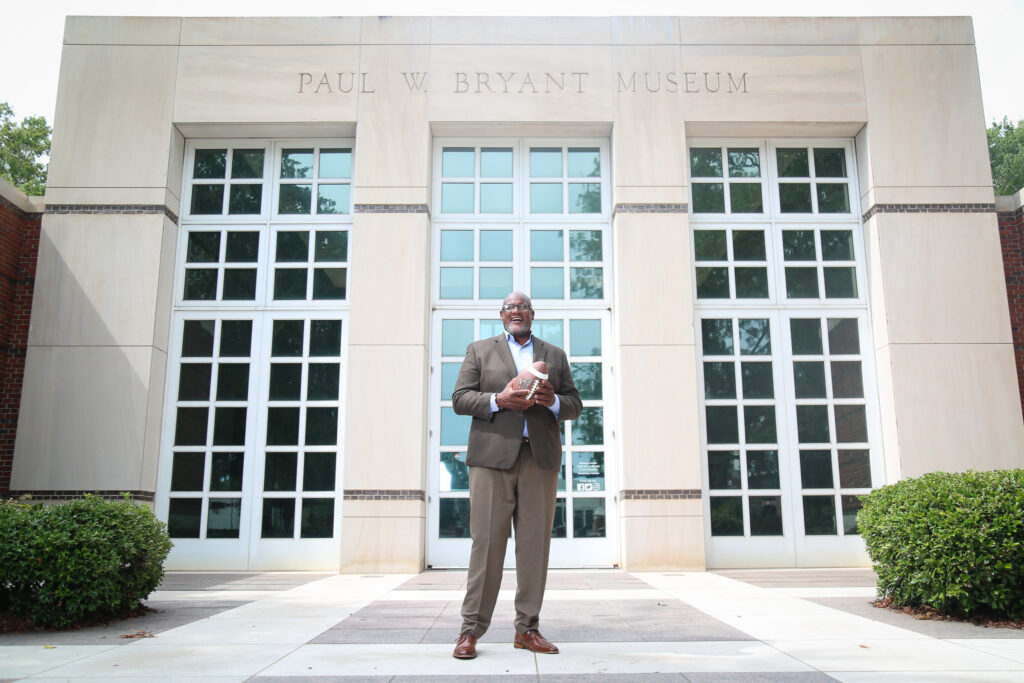

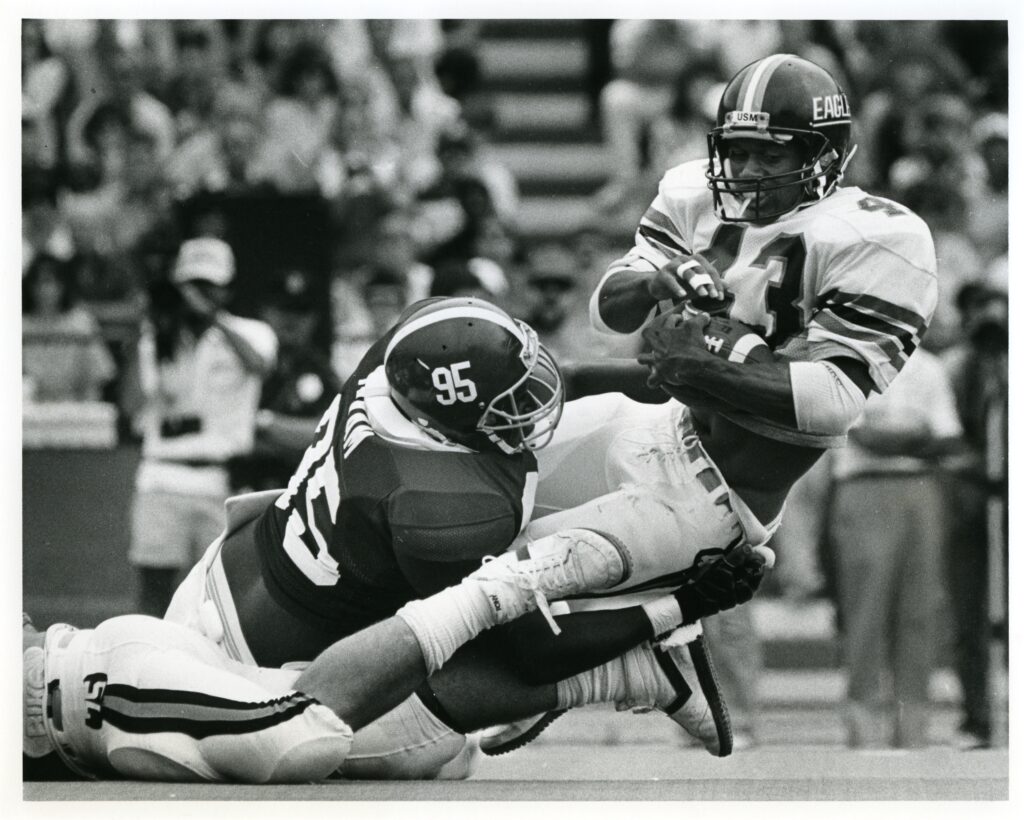

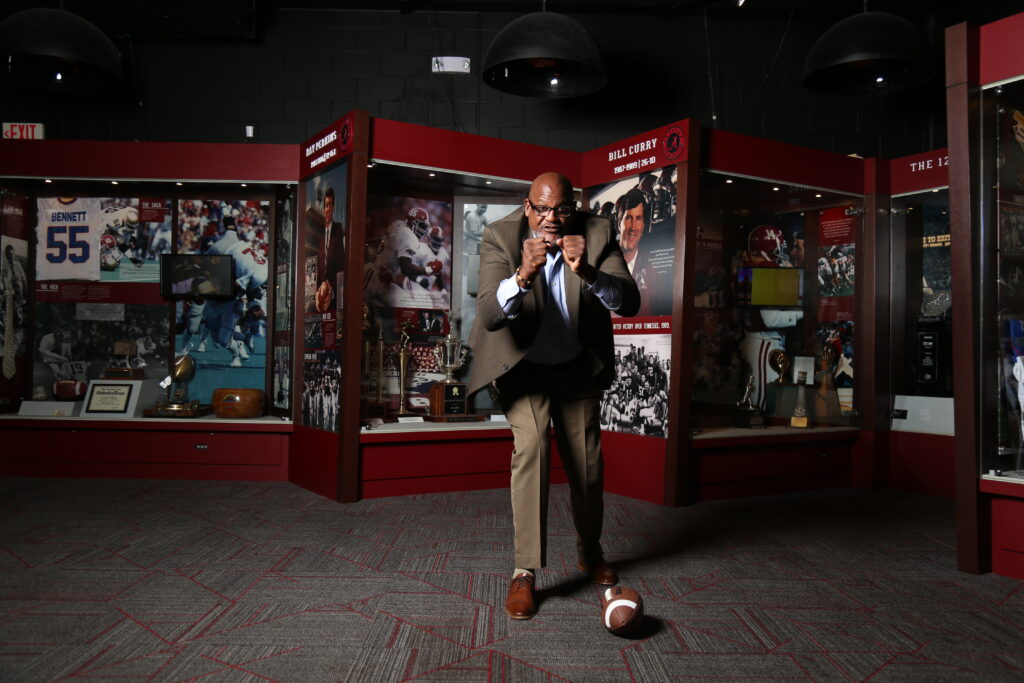

In 1989, Thomas Rayam made one of the greatest plays in Alabama football history, blocking a field goal in the waning moments to beat Penn State. It was a moment that changed his life. Every bit as compelling as that moment, however, is Thomas Rayam the man. Here’s his story.

I wasn’t supposed to block it…it really shocked me that I blocked the ball, but it was a feeling of Kairos, like in the Bible. I felt myself beyond the line of scrimmage and hearing Larry New, the defensive line coach at the time, saying, ‘get your hands up if you don’t get.’ I felt myself as I was beyond the line of scrimmage…I was so far beyond the line that when I turned this way…when I did that (stretches out his hand), at the right time, the ball hit my hand. I’m actually reaching, stretching….and when the ball hit my hand, I thought that I had maybe slapped a helmet.

Imagine a young boy sitting under an oak tree in the backyard of his home in Orlando, Florida. It is 1986, and the boy has the weight of the world on his shoulders. In just a few short hours, he has a decision to make, as many of the top college football programs in the country are turning over in his mind like cards in Rolodex. Will he choose Florida State? Miami? Oklahoma? Or how about Alabama? As he is contemplating his future, his mom—the woman who had been there by his side and had never steered him wrong—walks outside to offer some words of encouragement.

Minnie Rayam had already had two sons leave the house and go onto successful endeavors: Curtis Rayam Jr., the oldest, was a successful opera singer in New York, and Hardy, another brother, went on to play football at Notre Dame. Needless to say, Minnie was no stranger to guiding her posterity to a bright future.

She was also no stranger to adversity. After having Thomas, she suffered from brain surgery that caused the left side of her body to be paralyzed and walked with a noticeable limp. Minnie continued to work outside of the home despite the challenges.

“Thomas,” she began that day in the backyard, “you’ve got a decision to make other than any of the kids who have come through this house.”

Thomas raised his head and looked with utmost respect at his biggest cheerleader, the woman who had carried him around in the womb, who’d swelled with pride watching her son crawl—literally crawl—to make a tackle on the football field. Then she said something Thomas would never forget:

“And my decision is that if you don’t go to Alabama, you’ll break my heart.”

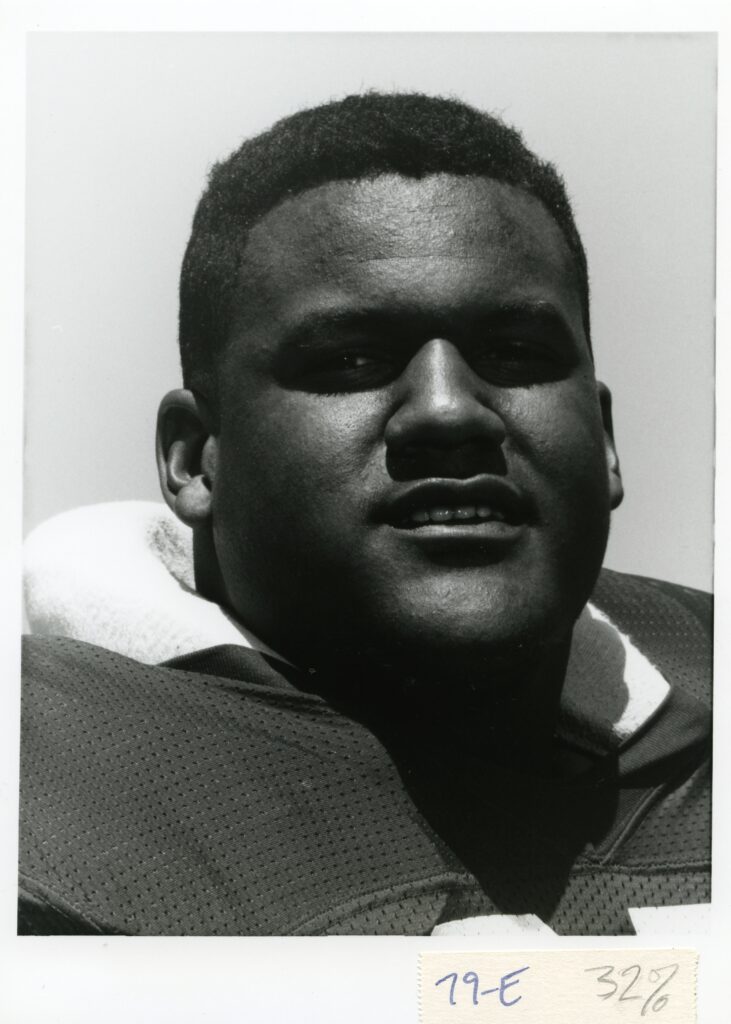

Thomas Leon Rayam was born with a gift. When the Creator constructed him, he made him tall and uncharacteristically large—his eventual six-foot-seven frame a perfect size for the game of football. Rayam grew up practicing the game by himself in that same backyard, and since the family income had to be spread among seven children, equipment often had to be of the makeshift variety.

“I had the big shoulder pads and the pads stuck in my pants,” Rayam smiles. “My mom was mad at me because I’ve got towels as my knee pads and I’ve got a helmet tied around my head.”

Rayam played quarterback all throughout his youth, and it wasn’t until he arrived at Robert E. Lee Middle School in Orlando that he believed he would do anything else. Coach Dale Carter convinced him otherwise.

Here’s how that conversation went the day Thomas arrived at the practice facility:

Carter: “Oh my, you’re a big kid! What is your name?”

Rayam: “Thomas Rayam.”

Carter: “Oh, you’re Hardy Rayam’s little brother. I know Hardy! Hardy’s at Notre Dame!”

Rayam: “Yes, that’s my brother.”

Carter: “You are going to be one of the best linemen.”

Rayam: “No, coach. I’m not a lineman…I’m a quarterback!”

Carter: “Son, look around the locker room. You’re the biggest person in here!”

Rayam was soon installed as the team’s center, his dreams of playing quarterback going out the proverbial window. He went on to play offensive line and later defensive line at Jones High School in Orlando—a school that had already developed a reputation for cranking out great football talent, including the Newton boys (Nate, Tim) who starred in the NFL. To be sure, this was no mediocre program of duds and also-rans.

“You had to pick your game up,” Rayam recalls.

Not to mention he was carrying the torch for the family as Hardy Rayam’s little brother. Indeed, there were some big shoes to fill.

I’m right here. The ball is actually right there (pointing). I’m here in my stance here. The guy who has the ball normally comes to the penetrating gap, which is right here. Mike Ramil is on this side. I’m watching the ball, and when he snaps I do this (clutching hands), into this guy’s chest. He goes that way, I came another step or two this way and turned…Boom! Straight on!

Rayam’s first taste of the recruiting process occurred in 1976, when Alabama head coach Paul “Bear” Bryant called the house asking for Hardy, and young Thomas answered.

“I’m like the little kid on The Blind Side. I get goosebumps even now,” Rayam recalls. “That made one of the largest impressions in the world.”

Thomas, like his brother Hardy, eventually became one of the top recruits in the state of Florida, being tugged on heavily by the aforementioned titans of Oklahoma, Miami, and Florida State—programs that found elite success in the 1980s and boasted head coaches now in the College Football Hall of Fame: Barry Switzer, Jimmy Johnson, and Bobby Bowden, respectively.

Early on, Thomas was leaning toward Florida State—the allure of playing for Bowden and the proximity of Tallahassee almost too good to pass up—but a visit from Alabama and head coach Ray Perkins changed the trajectory of his decision.

“Coach Perkins came to the house one night. We had black eye peas, rice, fried chicken, cornbread, okay?” Rayam remembers. “Coach Perkins got in line behind me to fix his plate, ate his dinner, sat on the couch, and took his shoes off. My dad was like, ‘this man really wants you!’”

That led to the moment underneath the oak tree in the backyard.

But Thomas had questions. After his mom implored him to choose Coach Perkins and Crimson Tide, Thomas inquired, “How are you going to get to see me?”

“I’ll be there,” she replied.

A mother’s heart, combined with a coach’s pursuit, led Rayam to choose the Crimson Tide.

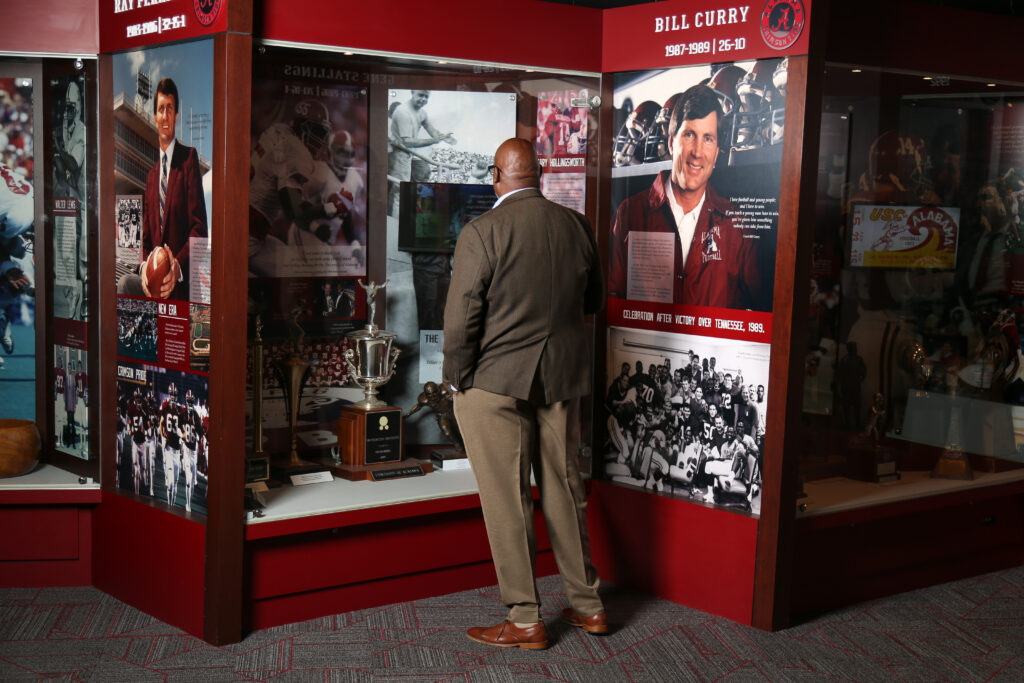

Tuscaloosa

Rayam arrived on the Alabama campus in the fall of ’86. Alabama was a program three years removed from the death of Bear Bryant and attempting to rise, phoenixlike, from the ashes through the leadership of Perkins, a Bryant apostle and former New York Giants head coach. That same year, Rayam sat in the stands as a freshman and watched eventual national champion Penn State march into Bryant-Denny Stadium in Tuscaloosa and manhandle the Crimson Tide by a score of 23-3. Three years later, Rayam would make history.

Perkins left the Alabama program after the 1986 season to become the head coach of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, and Rayam’s new coach was a former Vince Lombardi pupil named Bill Curry. Curry and his defensive staff quickly installed the vaunted “RAM” defense, and the lynchpin of the whole operation was a roaming man-child from Miami, Fla., named Derrick Thomas. Rayam had the distinct luxury—and pleasure—of toiling beside Thomas (nicknamed “DT” or “BB” if you knew him back in Florida, as Rayam did) for the next few years.

Rayam, who would get to know Thomas on a personal level, remembers D.T. imploring, “Big Dog, you crash ‘em hard. Big Dog, you just crash that corner really hard, and I’m coming off.” During the years from 1987-89, the ‘Bama defense held opponents to 15.4 points per game (19th in nation), 13.3 (10th in nation), and 15.3 (18th in nation).

I didn’t have to jump, because when I hit, I drove him back so far…all I had to do was turn. (I was) literally stretched out…there was no jumping through the air…just reaching high as I possibly can.

In 1989, Alabama waltzed into State College, Pennsylvania, with an undefeated record of 6-0 and fresh off a 47-30 victory in the “Third Saturday in October” against Johnny Majors’ Tennessee Volunteers. By then, the Alabama-Penn State game had become a mainstay, the two teams playing in consecutive years from 1981-88 and the Tide holding a 5-3 edge in the rivalry of the North-South powerhouses.

The game that afternoon in central Pennsylvania was tight, but it was the Nittany Lions who appeared to have the edge as placekicker Ray Taurasi lined up for a game-winning field goal. Listen as Alabama radio announcers Eli Gold and Jerry Duncan describe the scene:

Gold: The football is basically at the goal line. It will be a 17-yard field goal attempt. This is less than an extra point as far as the distance is concerned, this football will be snapped from the half yard line:

Duncan: Alright Eli, we gotta block it.

Gold: Gotta block this one!

Duncan: If you ever blocked one, you’ve got to block this one.

Gold: This will be a 17-yard field goal attempt. In is Ray Taurasi, the senior from Pittsburgh. Thirteen seconds to go. The snap is up. The spot…blocked!

Duncan: He blocked it Eli!

I was truly hurt that game. I had a fractured ankle and was told not to play that week. I played anyway and had one of my better games. I think I had about nine tackles and made one of the game winning plays. We all had a great game. Lamonde Russell had a stellar game. The offensive line with Trent Patterson and Terrell Chatman and Vince Strickland and Robinette and Roger Schultz…those guys played their butts off. We had a lot of people come up big. Siran Stacy came up huge! A lot of people… I could just go on and on and on. When you watch that film, I mean the block is just what sealed the deal, but if you look at that game, the Steve Webbs, the Charles Gardners, the John Mangums, and, most importantly, Willie Wyatt. If Willie hadn’t have tackled Blair Thomas and tripped him up the play before, there is no desperation block.

For Alabama, it was pandemonium. For Penn State, heartache.

Coming back to campus, Rayam, for a time, became somewhat of a celebrity, and he would soon begin to see how one moment could change a person’s life. The night the team arrived back from the Penn State win, Rayam saw assistant coach Larry New walking towards him. “Get your butt in bed! Don’t you go out nowhere. Nowhere!” Rayam recalled New saying. This opened the door for teammate Vince Strickland to hit the Tuscaloosa strip that night as—you guessed it—Thomas Rayam.

“Vince said he had more fun as Thomas Rayam that night that he ever had in his life on campus! Everything was on the house for him that night,” Rayam laughs.

For the next few days, months, and years, the name Thomas Rayam would always be mentioned in the same breath as the “desperation block” at Penn State. But his story didn’t conclude there.

Rayam was drafted in the tenth round of the 1990 NFL Draft by the Washington Redskins. He played in the NFL from 1990-93, spending two seasons with the Redskins and two with the Cincinnati Bengals. After returning to Birmingham in 1995 to play for the upstart Birmingham Barracudas of the Canadian Football League (CFL), he played for the Edmonton Eskimos, Calgary Stampeders, and Toronto Argonauts. He retired after the 2002 season.

In his post-playing life, Rayam found success in the medical sales industry and has served for many years as a volunteer coach for the Thompson High football team, teaching young athletes the fundamentals of the game that he learned though great coaches along the way. He also established Team Rayam Outreach, a nonprofit organization focused on empowering and challenging youth physically, mentally, and spiritually to grow and excel in athletics, school, and life.

Though Rayam may be known for a play called the “Desperation Block,” there is nothing desperate about the way Rayam lives his life, save for the way he depends on God to get him through each day. Rather, his life is very intentional. Calculated even. He pours into his children— Brandon, TJ, Madison, and Jalen—runs his medical sales route (which now covers the entire state of Alabama), and tries to stay grounded in his faith. This life he’s cobbled together here in Alabama is a by-product of a mother’s encouragement that afternoon in the backyard.

Rayam reflects on a quote that was posted just above the front door of his childhood home that read:

Only one life ‘Twill soon be past,

Only what’s Done for Christ will Last

“This is back when salesman came to the house and sold clocks, pots, pans, and things like that,” Rayam said. “One day, my mom bought that quote and stuck over the door so me and my siblings could read it on our way out of the door. Later, we had a flood in the house and my brother put it in a box. I found it and have it with me now on my desk to remind me that Mama is still influencing me.”

Sadly, Minnie Rayam passed away in 2000. Rayam frequently goes home to Orlando to reminisce and refocus in that same space in which his mom intreated him to go to Alabama so long ago. It’s been a decision he’s never regretted.

“I owe a lot to Tuscaloosa. I owe a lot to Alabama football. It was a great decision to come to Alabama,” Rayam says. “My mama hasn’t steered me wrong yet.” TG

Images by Al Blanton, courtesy Thomas Rayam and the Paul W. Bryant Museum.