“I wanted my players to like me five to 10 years after they left because they understood what I was trying to do, what our team principles were, how you treat other people and how to respect the things you’ve gotten in life.” – Bill Jones, former head basketball coach, Jacksonville State University

The jail cell door clanging shut behind him still rings loudly in his ears.

Although it’s been more than 60 years now, Bill Jones remembers when his father, “Big” Bill — all 6-foot-7 and 310 pounds of him —wanted to deliver a life lesson to his then 13-year-old son, and as the police chief of Guntersville, Ala., he had just the avenue to do so. Big Bill simply found a dirty jail cell with a passed-out drunk and a broken urinal, and put the youngster inside.

Hours later, the boy remained incarcerated; the drunk had awoken and was babbling incoherently. Big Bill was still nowhere to be seen.

“He finally came and got me, and when he did I was really mad, and I said ‘What did you do that for?’” Jones said. “He said, ‘Boy, that’s the way jail is, and if you ever get put in it, I’m not coming to get you. Now I think he would have. Back then I wasn’t so sure.’ Dad was what I call a critical analyst. I think that’s what made me what I am today.”

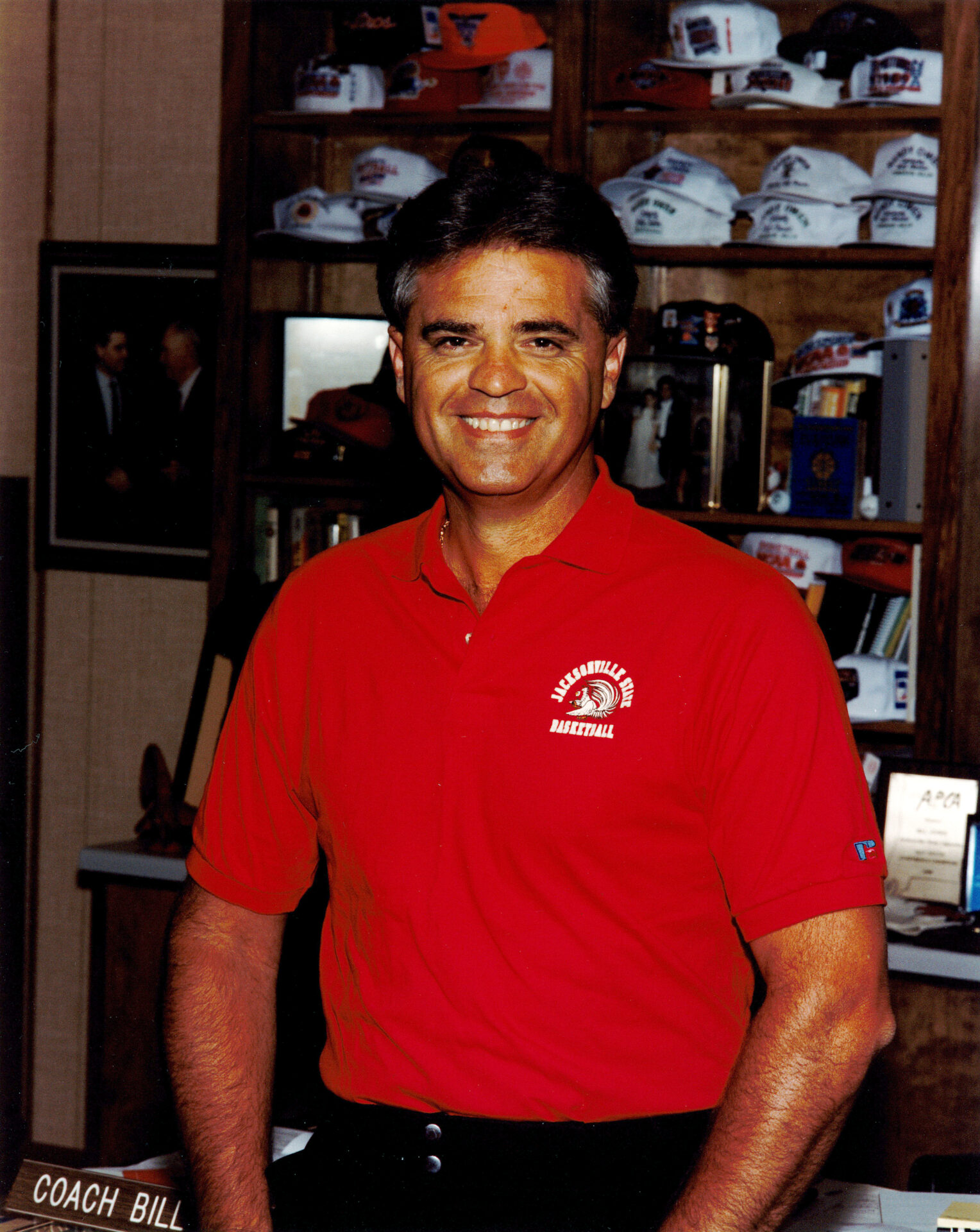

What Jones, former NCAA Division II national champion basketball coach at Jacksonville State University, is today amounts to many things, but the word used most to describe him in all facets of his life is “winner.”

The Watch

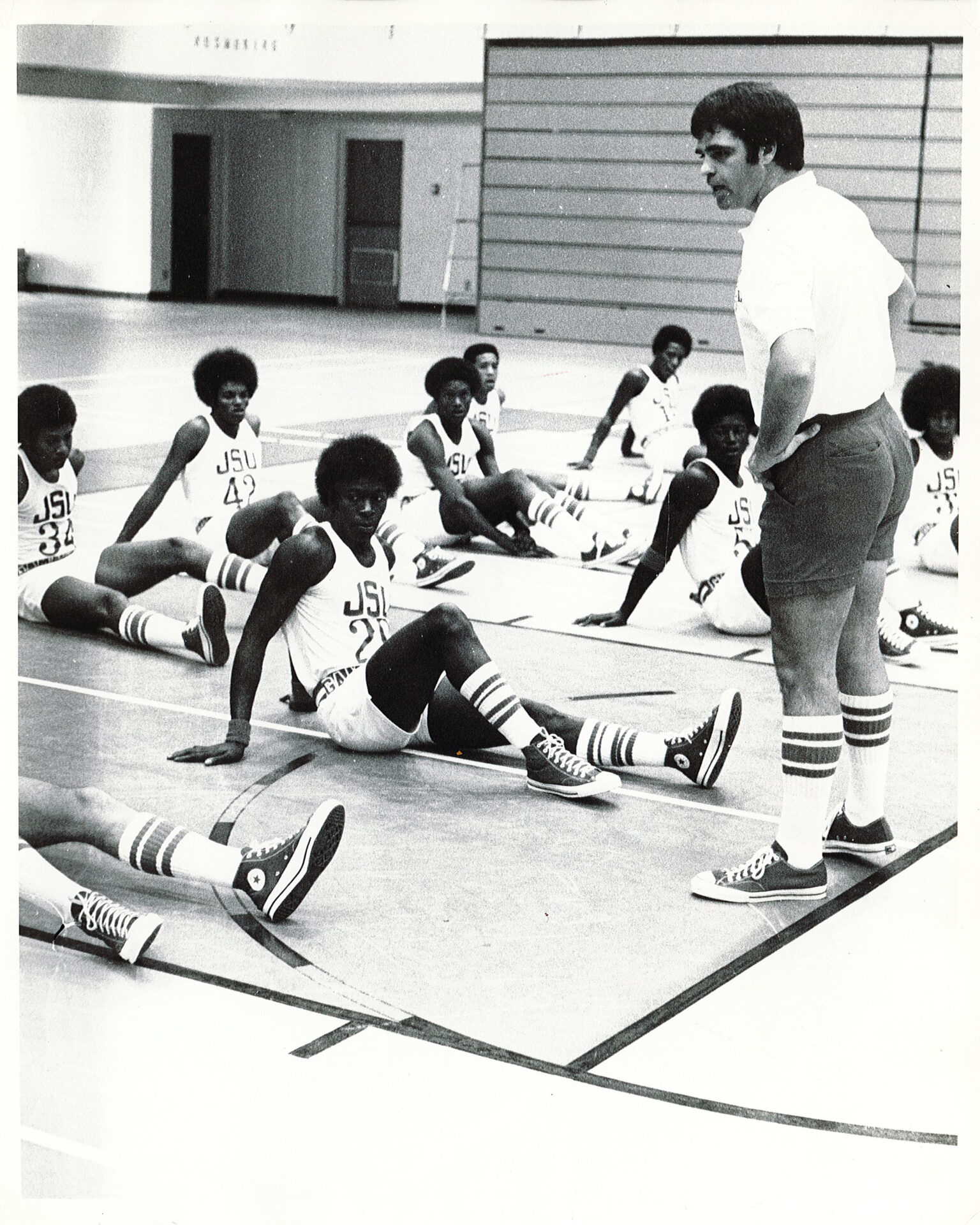

Bill Jones hates to lose, so much so that he “wanted to quit after every loss” of his 26-year coaching career. First at Florence State University and then Jax State, Jones posted a stellar 477-226 record (a 68-percent winning percentage).

As a kid, he turned over Chinese checker boards when it was obvious he was going to lose against his sisters. “I’d flip them over and go the other way because I hated it so much,” he said.

The stories of Jones’ competitiveness are legendary. Card games on bus trips. Long drives on the golf course. Home runs on the softball field. Talk to anyone who has known him for any length of time and they will surely mention his obsession with winning. “Before practice Coach Jones would shoot free throws while the team was warming up, and while he was doing it he would be talking about what had gone on during the day, asking about your class or telling a funny story,” recalled Charles Ponder, an equipment manager during Jones’ final two seasons at JSU in 1995 and 1996. “He wouldn’t hit any of the rim, and he’d shoot about 90 percent every time. Well, during one of my first practices with him, he came over and said ‘Let’s see who can make the most free throws in a row without missing.’ I thought I was a pretty good free-throw shooter so I said OK.

“Then he said we would bet watches. He had on a really nice watch and I had on a Casio, but it didn’t matter because it was going to be his anyway. I hit my first eight before I missed, then he stepped up, and I swear he hit seven, eight and nine with his eyes closed. He came over and said, ‘I own your watch but you can keep wearing it.”

Later, Jones used the watch as a teaching tool in that day’s practice.

“He was explaining to the team what would happen if they did something a certain way, and he said ‘If you do this, I bet you my house, so-and-so’s car and Charlie Ponder’s watch that I own, this will happen,’” Ponder said. “The wit it took to throw something that just happened into the lesson he was teaching that day still sticks out in my mind more than 20 years later.”

Another quick story about Jones’ drive to win comes from long-time JSU Sports Information Director Mike “Scoop” Galloway. “Even crappie fishing was a competitive sport when Bill was involved,” Galloway said. “If you caught one bigger than him, you weren’t leaving until he caught one bigger than you. We were fishing off a bridge one time in Centre, Ala., and I finally got tired and put my pole down and said, ‘Go ahead and catch one bigger than me so we can go home.’ I didn’t want to catch a bigger one or we would have been there all night. There wasn’t much traffic on that bridge, but the police finally ran us off about 11 p.m.”

That competitive edge certainly carried over to the practice floor, the locker room, and the sideline. It manifest itself in many ways, especially at JSU, where he posted 449 career victories, 11 seasons of at least 20 wins, three Coach of the Year honors in the old Gulf South Conference and the coveted national title in a dream season of 1985.

“I don’t think any of my players liked me very much when I was coaching,” Jones admits. “I don’t think any of them would say, ‘He was a player’s coach.’ I still want somebody to give me a definition of a player’s coach. Does that mean they get to do whatever they want in practice or at curfew time? Does everybody talk good about you? What does it really mean?

“I wanted my players to like me five to 10 years after they left because they understood what I was trying to do, what our team principles were, how you treat other people and how to respect the things you’ve gotten in life.”

And they do.

Tough but Fair

After an All-State career at what was then Marshall County High School in Guntersville, “Little” Bill—at 6-foot-2 and 160 pounds—chose Snead State Community College to begin his college career. Two years later, he had grown to 6-4, earned All-State and All-Region junior college honors and moved on to JSU, the place that would grab his heart and hold it to this day.

As a Gamecock, he continued to grow in stature (gaining another inch, to 6-5) and in confidence as a basketball player, particularly as a shooter. In his two seasons, Jones set a then-school record with 31 consecutive free throws made, poured in 886 points and led the team in scoring both years as the Gamecocks claimed successive Alabama College Conference titles. He was named to the ACC All-Conference team in 1964-65 and 1965-66 and chosen All-American in 1965-66.

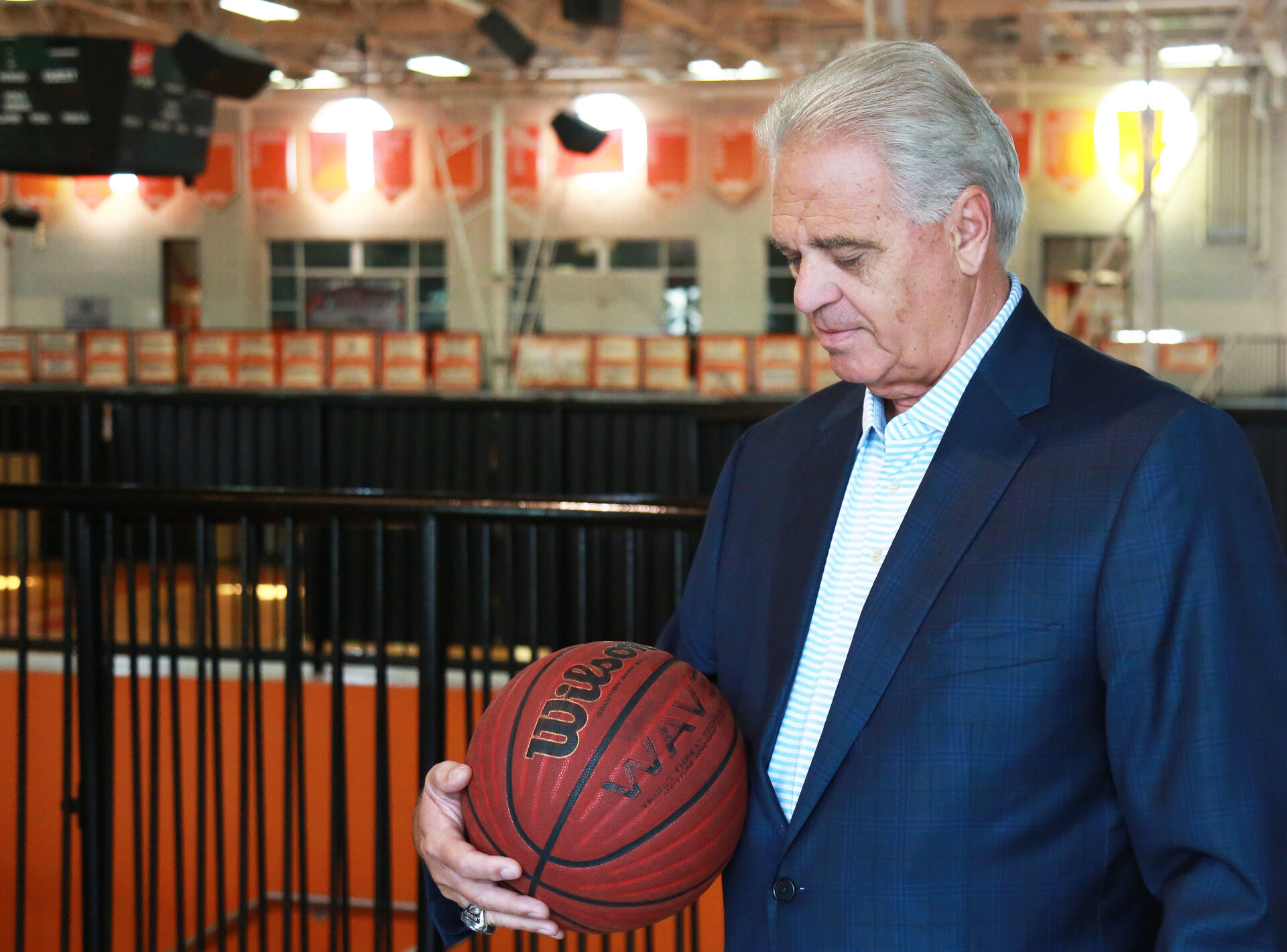

To this day, he is the only JSU men’s basketball player ever to have his jersey retired, and his No. 12 will soon hang again in the rafters of Pete Mathews Coliseum.

As a tribute, current JSU coach Ray Harper has also started awarding the number to a player he feels embodies the attributes for which Jones stood. The number can once again grace the playing surface that in late February 2018 was officially named Bill Jones Court.

“During my playing days before it was retired, I wore No. 12, too, and he always used to tell me ‘A lot of special people have worn that No. 12. You’ve got to fill it out right,’” said Earl Warren, a senior guard and leader on the 1985 national championship team. “I was like, ‘OK, coach, I promise I am going to do my best’ and I did, too, because that’s what you wanted to do for Coach Jones.”

Warren witnessed his coach’s competitive side up close and personal. He saw the hard edge, the “tough love” point blank. Warren also saw the undying devotion and the unending pursuit of excellence the man instilled in his people and his program.

“The thing I appreciate more than anything about Coach Jones was that there was never any double standard,” said Warren, now the director of JSU’s University Development office. “He was very fair, and what went for you went for all 15 guys on the team and vice versa.”

Warren vividly recalls seeing his coach dismiss a player with all-conference potential because of outbursts directed at others. “He ran off one of the best players I have ever seen, a 6-10 guy who would have dominated in the Gulf South Conference,” Warren said. “He came here one summer from another school where he had apparently had some anger management issues, and in practice he jumped on a manager and even one of his teammates. Coach Jones got him over to the sideline and told him, ‘I want you to go get your stuff and get your butt out of here.’ He just would not tolerate anyone who was not going to display the kind of character he was looking for.

“I always tell people that my high school coach taught me how to be a good basketball player, but Coach Jones taught me how to be a man.”

A Second Chance

Jones admits that one of the best players ever to dribble a ball for him was “a second-chance guy.” His name was Robert Spurgeon, a stalwart on the inside for the 1985 champs and No. 8 on the Gamecocks’ all-time scoring list with 1,357 points. His JSU tenure did not start well, however.

As a 6-5 freshman forward from Cedartown, Ga., Spurgeon was late to his very first Gamecock practice and found the doors locked. A manager, a fellow freshman, let him in, and Spurgeon was walking to the locker room when Jones stopped him. “I said, ‘Where are you going?’ and he said, ‘I’m going to get dressed for practice,’” Jones recalled. “I said ‘You’re not practicing with us today. You’re late, and you’ve got to pay the penalty for it.’”

The penalty was that the player would have to take two 10-pound weights upstairs to a track that circled the upper level of Pete Mathews, start running, and continue running until the practice on the floor below him was complete.

“I told him that he could carry them anyway he wanted but if he put them down it would double his time,” Jones said. “So if we practiced for an hour and 45 minutes, he had to run with those 10-pound weights for an hour and 45 minutes. He said he wouldn’t do it so I told him to go to the dorm, get his stuff, and be gone by the time the players got back over there. And he did.”

A year later, the coach looked out his office door, across Pete Mathews towards a figure silhouetted against a glass door by bright sunlight. Jones couldn’t tell who it was, and admits he frankly didn’t give it much thought until he heard a knock on his door.

It was Spurgeon, and he had come with a message and mission. The player wanted to tell Jones he had messed up, and Jones agreed. He wanted to apologize, and Jones accepted it.

Spurgeon was headed to a junior college to continue his career but wanted to find out first if there was any chance he could return to JSU, and Jones said “sure.” “I give second opportunities to people if they understand what they did was wrong and if they vow they are never going to do it again,” Jones told him.

That was great, Spurgeon said, and as they stood to shake hands, the player told him he would be there in the fall.

Not so fast, big guy.

“You still owe me,” the coach said.

Jones handed him the 10-pound weights. With nobody in the gym but player and coach, Spurgeon ran for an hour, soaking his street clothes through and through with sweat.

“He was a tough son-of-a-gun,” Jones remembers. “Four years later we won a national championship because he did exactly what I asked him to do. After that episode, he was one of the most honest, forthright, team-oriented guys I ever had.”

As it turned out, Spurgeon had been standing on a street corner in Cedartown when a drive-by shooter took out his best friend. At that moment, he decided he was getting out of there and going back to school.

“It was a second chance for him,” Jones said. “He realized it, and I was glad to award it to him, not because we ended up winning the national championship, but because I think it changed his life.”

A Dream Season

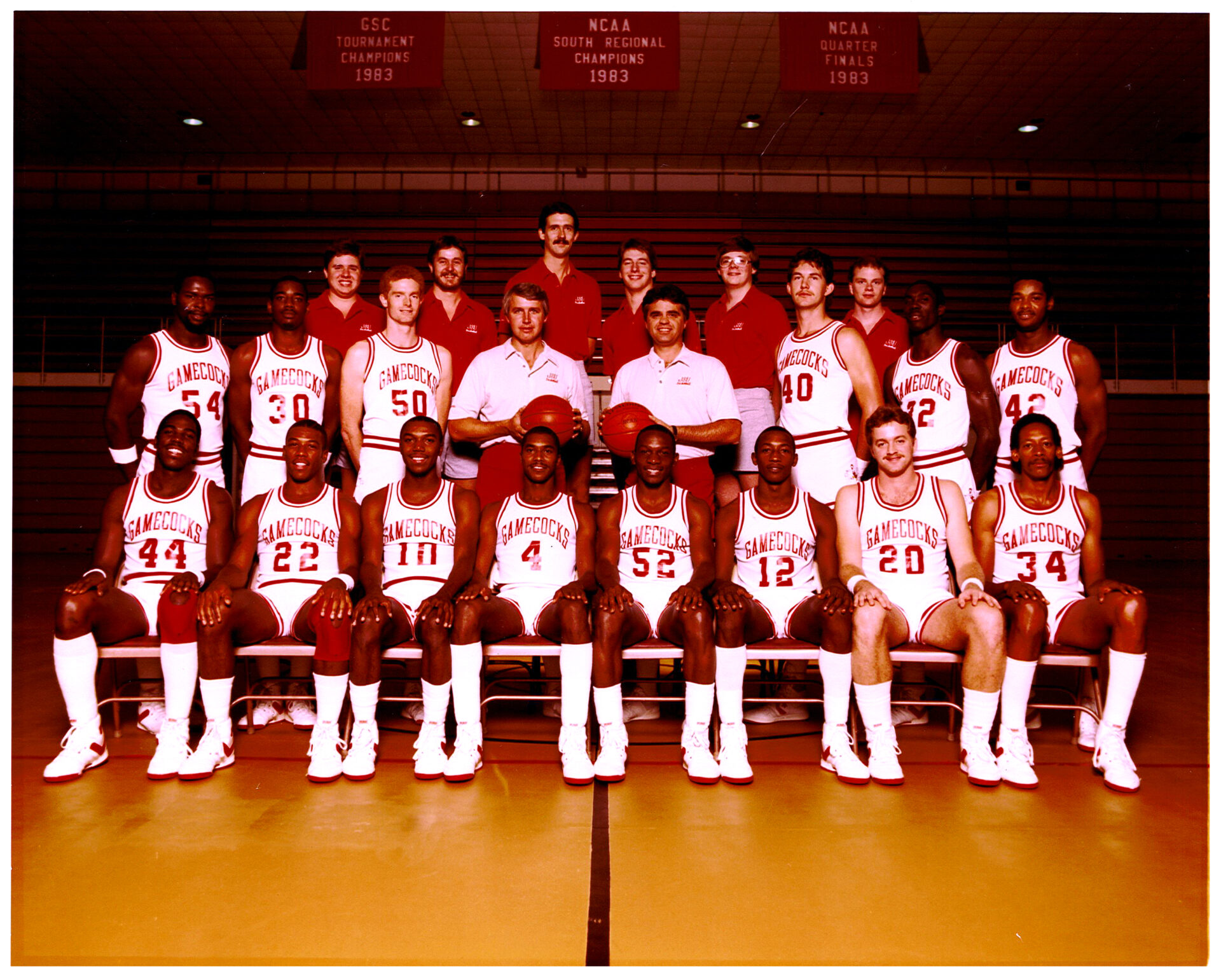

The 1985 national championship was the zenith of JSU’s basketball history and Jones’ coaching career, but it began with a whimper.

Returning five starters from teams that had won 47 games and reached the Division II Elite Eight and Sweet Sixteen the previous two seasons, plus new signee Pat Williams, a guard from Jefferson State who was the reigning Alabama Junior College Player of the Year, the Gamecocks were poised for greatness.

Unfortunately, they sensed it.

“We knew we were going to be good so we had this confident air about us,” assistant coach James Hobbs said. “But some people probably looked at us and said we had gotten arrogant. We were thinking we had won 23 and 24 over the last two years. We’ve got everybody back. We’re going to be hard to beat.”

That bubble burst in the season opener, a matchup with a good—but not great— NAIA team, Belmont Abbey, in the Armstrong State Classic in Savannah, Ga. The Gamecocks slept-walked through the game and when Belmont Abbey’s Charles Hubert, one of the top NAIA guards in the country that year, dropped two free throws with 3 seconds left to clinch a 61-60 victory, the Gamecocks were shocked back to reality.

“I was very disappointed,” Jones said. “In fact, it was more than that because the next day, at our practice before the game that night, I made our cheerleaders cry in the gym. It didn’t mean that much to them, and I understood that to a point, but I still got on them pretty good. I just knew we were a better team than what we had shown.”

Most importantly, so did the players, who regrouped and set out on a 31-game run to glory that is still the stuff of JSU legend.

“That was the turning point for our whole season,” Hobbs said. “We were a heavy favorite. They had one really good player, and we had six and they knocked us out in the end. Our guys go in the dressing room after it was over and they’re looking at each other like, ‘We’re not going to let this happen again. We are not going to show up and let somebody beat us that’s not a lot better than us,’ And they basically played with that chip on their shoulder the rest of the year.”

Starting with a 90-79 dispatching of Armstrong State the next night, JSU ran off 16 straight victories before running into its first real speed bump against Delta State and future Southeastern Conference standout Gerald Glass on a late January night.

Trailing 73-71 at home with 12 seconds left, Robert Guyton converted a one-and-one opportunity to tie it, and Delta State missed three shots from within 8 feet at the buzzer to send the game to overtime. Then it was Delta State cutting it close with 12 seconds remaining as a jumper made it 80-79 JSU, but Warren and Guyton hit clutch free throws in the last 10 seconds to give JSU an 84-81 win and a Gulf South Conference record 17th straight victory.

The Gamecocks then ran off another 11 straight wins to advance through the South Central Regional and back to the Elite Eight. That’s when things really turned magical.

JSU drew a trip to Cape Girardeau, Mo., to face Southeast Missouri State in what may best be described as the “Miracle in SEMO town.”

With 12 minutes left, the Gamecocks trailed 58-45. With 3 minutes to go, all five players on the floor had four fouls and Warren and super sixth man Williams had fouled out. With 16 seconds left, JSU trailed 79-76, and in the days before the three-point line, looked to be done. But Melvin Allen, the team’s leading scorer, hit a jumper with 8 seconds left to make it 79-78 and Bret Jones fouled SEMO senior Chris Arand with 6 seconds left. Arand missed both shots, and Kelvin Bryant rebounded the second miss and outletted to Jones, who found Allen streaking up the right side just over the mid-court line.

Allen took one, maybe two dribbles and, with three SEMO defenders in his face, let fly a shot that swished through the net as the buzzer sounded.

Now 29-1, JSU moved on to Springfield, Ma., and downed Kentucky Wesleyan 72-61 in the semis to set up a meeting with South Dakota State and 6-foot-9 Mark Tetzlaff, one of the nation’s best players, in the championship game.

Again, fate’s kiss was kind to the Gamecocks.

Trailing 71-64 with 2:14 left and nation’s longest winning streak and the title seemingly out the window, Jones’ bunch didn’t panic. Instead they smothered SDSU defensively and patiently chipped away on offense until a short jumper by Williams made it 72-71 with 44 seconds left.

SDSU tried to run out the clock, but JSU only turned up the pressure, and with 5 seconds left, Williams swatted an SDSU pass near the free-throw line, and Warren grabbed it and was fouled. He then calmly sank two free throws to ice an eventual 74-73 win.

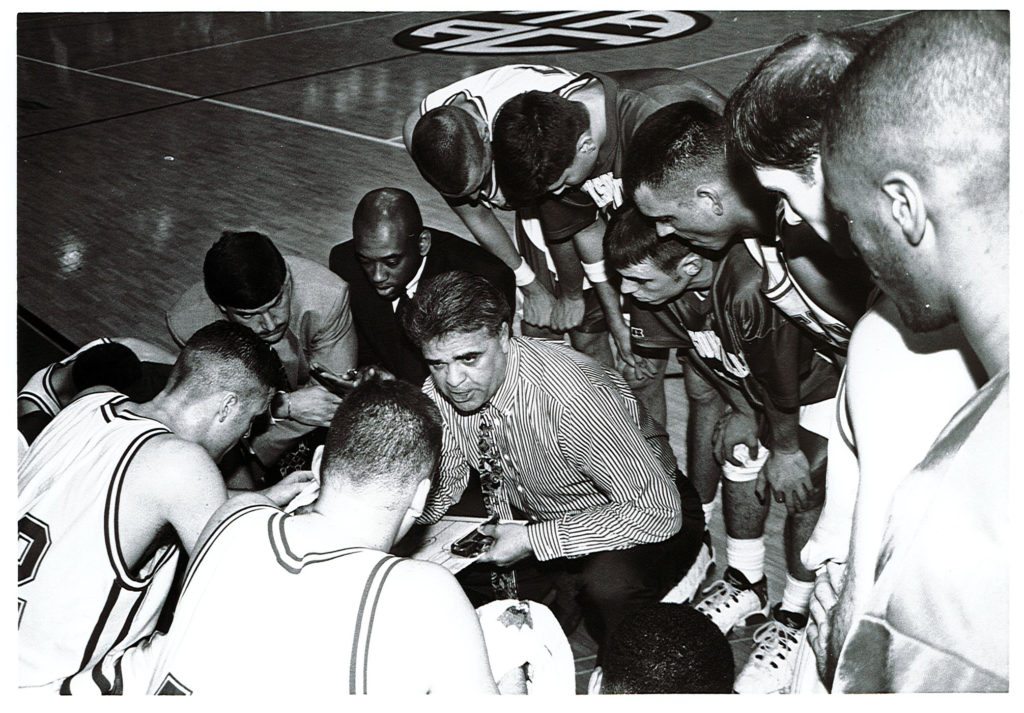

In the end, preparation plus poise equaled a place in JSU history, Jones said. “I called a timeout during that stretch, and I’m standing outside the huddle, and I think it was Earl Warren I heard say, ‘They’ve got the lead. We know how hard we can come back. We’ve got them right where we want them,’” Jones said. “After hearing that, I walked in and all I said was ‘Let’s go!’

“We went back on the floor, we knew our defensive assignments and we just continued to peck away until we finally got the lead at the end. We were behind but it didn’t mean anything. If that team was behind, that’s when the other team needed to be afraid because they’d find a way to beat you.”

As Warren recalls, “The good Lord had a special place for us that year.”

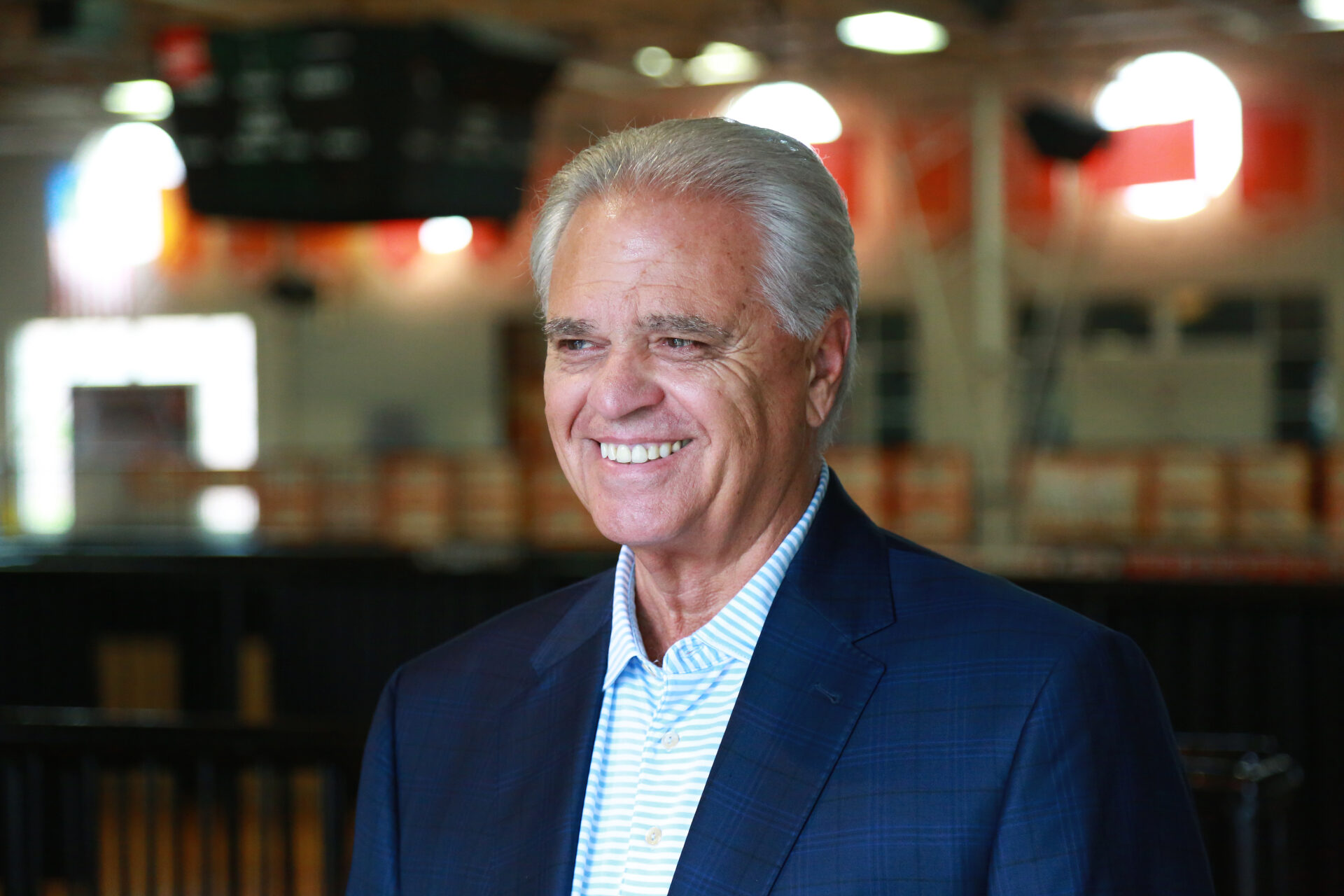

One Straight Shooter

Calling the championship game for ESPN was Dick Vitale, and he somehow saw things a bit differently than most everyone else involved. “In the interview at courtside after the game he told me he thought our switch to a man-to-man defense at the end was a really good move,” Jones said. “I told him I appreciated that, but we weren’t in a man-to-man, we were in a triangle-and-two. Vitale told me I may have thought we were in a triangle-and-two but that he didn’t think our kids thought we were.”

At a commercial break, the two went to the monitor and after further review, Vitale admitted the obvious. “He said, ‘I’ll be damned, you were in a triangle-and-two,’ but when we went back live on camera, he never mentioned it,” Jones said chuckling. “So every time I’d see him at a Final Four or somewhere like that he’d say, ‘I know coach, you were in a triangle-and-two.’ Well sure, I knew what we were in. We used that triangle very effectively, and it’s something I still give to a lot of coaches to this day.”

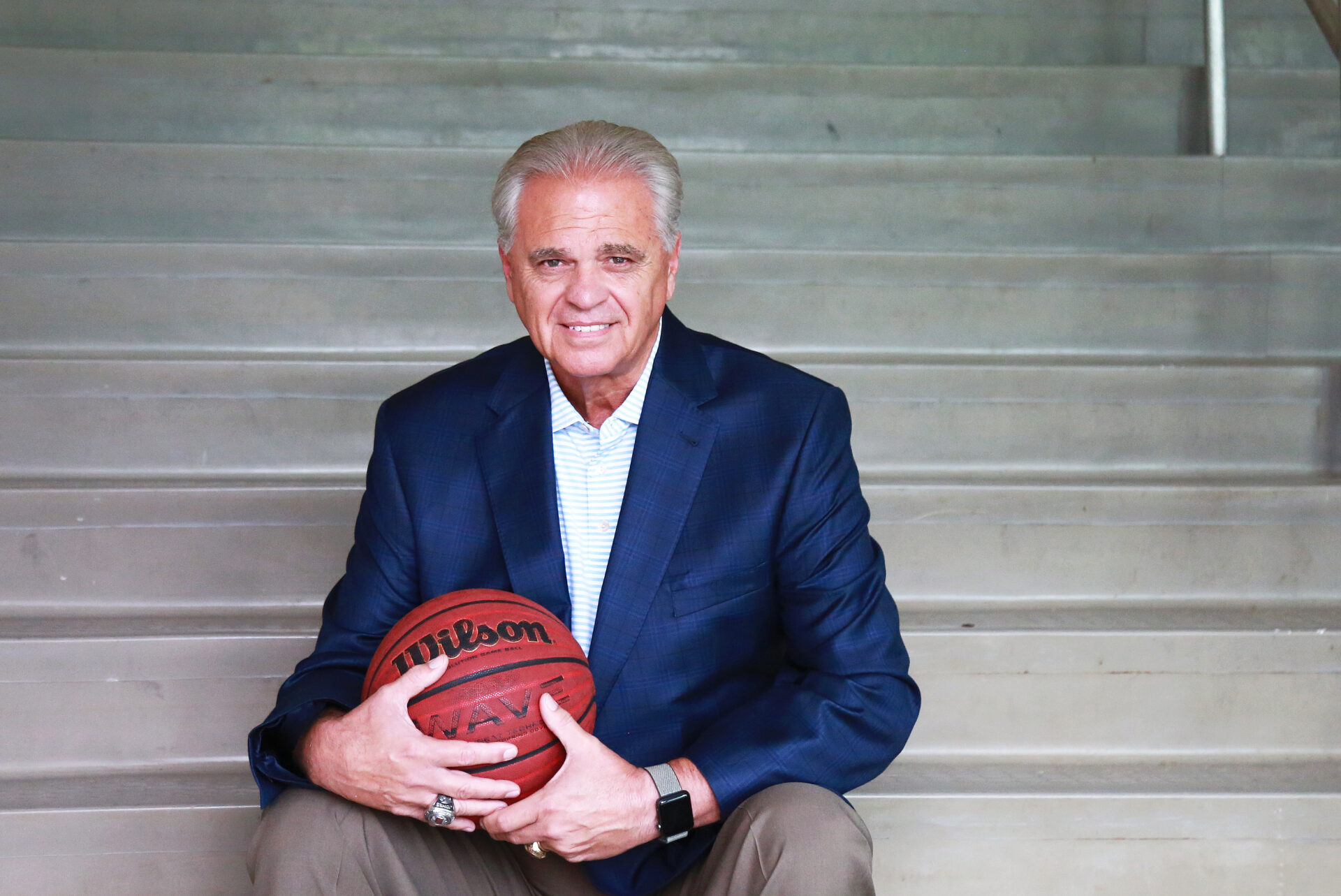

Upon his retirement after the 1997-98 season, Jones found himself somewhat at a loss as to what to do moving forward. He soon learned, however, that coaches and players at all levels were eager to learn from a national championship-caliber coach.

Former players and assistants like Warren, who coached at Donoho High School in Anniston, Ala.; Johnny Pelham, head man at Asbury High School in Albertville, Ala.; and Charles Burkett, now the head coach at Hoover High School, sought out their mentor to help their programs. College coaches like UAB’s Jerod Haase and others did so as well. After a while, Jones found himself serving as “critical analyst” to a whole generation of Alabama hoopsters.

“I tell the coaching staff up front that I’m not a back slapper coming to tell them how good they are,” Jones said. “I’m the guy who tells them what they need to do differently and what they can do to help themselves, a player, or their team. Most take it very well. Some don’t, but people shouldn’t ask questions if they don’t really want to know the answers.”

Many, like Burkett, the Gamecocks’ leading scorer in 1990-91 with 514 points and 13th on JSU’s all-time scoring list with 1,317, admit the columns of their coaching careers are built on foundations laid by Jones at JSU. “He’s forgot more basketball than I will ever know so I certainly take advantage of that,” Burkett said. “My fundamentals in everything I do come strictly from Coach Jones. I have gone back to the playbook from my Jacksonville State days many times to change up things and give us a different look.

“He’s like a father to me. He’s a best friend. There aren’t too many days that pass that we don’t communicate in some way, and I think he shares that openness with everyone, whether it is about basketball or life in general. I know he’s at my disposal, that I can call him 24-7 and he’s going to be there for me, and he’s going to be honest with me. I feel like I have an advantage over a lot of people in a lot of things for that simple reason.”

Another quick story from Galloway drives home Burkett’s point. On March 19, Galloway had just returned from a trip to Birmingham for a three-week checkup following back surgery when the tornado that ravaged Pete Mathews also took his home in the surrounding community. “I lost my house in the tornado, and the first person to get here to help from Birmingham was Bill Jones,” Galloway said. “In my book, there are none finer.”

The Right Decision

After graduating from JSU in 1966, Jones gave professional baseball a try as a Pittsburgh Pirates free agent, but a torn rotator cuff ended that adventure only a few weeks into training camp. His next stop on a winding career path was as a collection agent for the IRS — a job that not surprisingly he hated —then he became a contract negotiator with the U.S. Army Missile Command at Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville.

Then came a call from his old Snead State coach Emmett Plunkett just after Christmas in 1968 with the devastating news that Plunkett had suffered a relapse of cancer and needed someone to take over his team. So Jones became a contract specialist by day and a college hoops coach by night.

Later came an offer to move to Florence State as a graduate assistant, so Jones quit the good-paying job at the Redstone Arsenal and moved to the Shoals area for $100 per month. Oh, and he got to pay to earn his own Master’s degree as well.

“I have never regretted that decision,” Jones said.

Neither have all those he has touched both on and off the court over the years.

Nowadays he serves on the Board of Directors of the Birmingham Tipoff Club, where they eat, sleep and breathe basketball. He’s involved with the group bringing the Houston Rockets to town for a preseason game next season. He’s the color analyst on eight or so Samford University broadcasts on ESPN3 as well as some area high school games on radio.

He was recently inducted into the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame, becoming the eighth with JSU ties to enter that prestigious institution. He’s a member of the JSU Athletic Hall of Fame, the Marshall County Sports Hall of Fame and the National Softball Hall of Fame in Oklahoma City.

He spends time with Sue, his wife of 44 years, his daughters, Jennifer and Ashlee, and grandsons, 10-year-old Jace and 6-year-old Blake.

Most of all, he still coaches basketball, his first love. During the season, which starts with summer play dates and ends when the last ball is bounced in early spring, Jones wears himself out attending practices, going to games, helping coaches and serving as an ambassador of the game.

“Beside my recliner, I’ve got a schedule that runs from the start of the season to the end, and I get physically exhausted during that time,” Jones said. “If you work with a coach or a team in practice you have to go see them play, so I watch a lot of basketball, I talk a lot of basketball, and I love every minute of it.

It’s my way of giving back to something that has been terribly good to me all my life.” H&A