Winter 1982-83

That winter, you got the sense that something was coming to an end, more so than something new was beginning. In fact, it already had—ended, that is—when on a glum day in December 1982, Bear Bryant tendered his resignation as the head football coach at the University of Alabama.

Bear Bryant leaving a football life was as if John Wayne had quit cowboying. The day he told us he was gone, he had finally done the one thing he had always preached against: He quit.

With Bryant’s goodbye, all the whiskey and the Skynyrd, all the polyester and the Naugahyde, all the goal-line stands and the pretty cheerleaders, all the winning and the rah-rah speeches, seemed to go with him. It was like a 25-year party had come to an end. Darned, if it wasn’t all so sad, Roll Tide in peace.

The massive sinkhole of a legend Bryant left at Alabama was simply too big for one man to fill. Everyone knew it. Heck, there wasn’t a coach in the country who wanted to try. But someone had to.

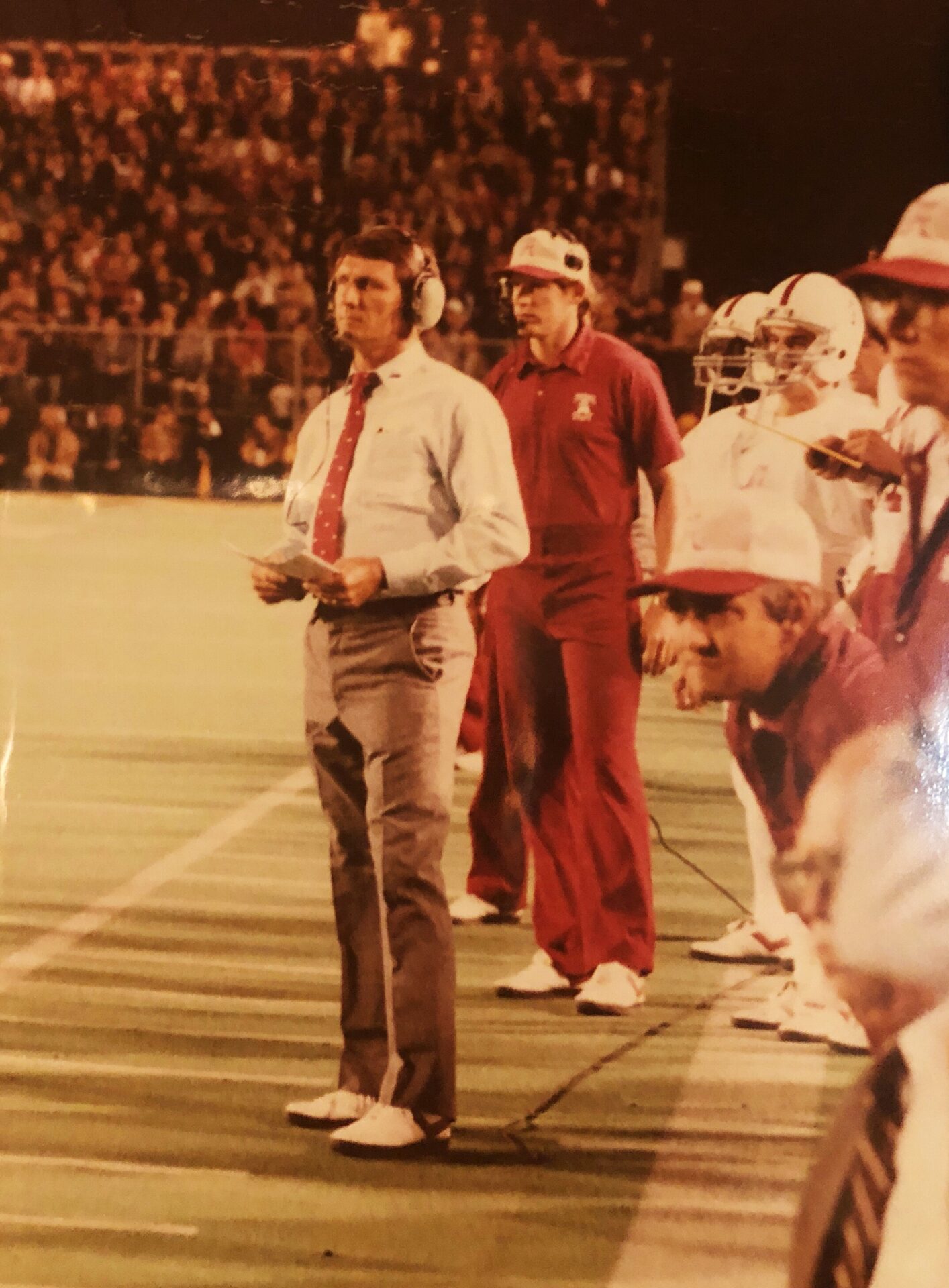

That someone was Ray Perkins.

A native of Petal, Miss., Perkins knew that Bryant’s greatness, his aura, could never be replicated, a point he conceded before he ever touched ground as the head coach in Tuscaloosa: “I’m following—repeat, following—the greatest coach in college football.”

But somehow, Perkins seemed to be the one guy who was unfazed at the challenge. Before leaving for Alabama, Perkins met with a friend, Bob Drake, just outside of Hattiesburg, where Drake expressed his concern about Bryant’s long shadow and Perkins’ inability to come out from under it. “Well, Ray looked at me with absolute confidence and said it didn’t bother him one bit,” Drake said. “Not one bit.”

If America did not understand the allure of Alabama—and Bryant—it was about to now. Perkins, who had previously been the head coach of the New York Giants, surprised the national press when in December he simultaneously tendered his resignation from a podium in East Rutherford, N.J. After all, why would anyone in their right mind leave the shine and panache of the Big Apple—the N.F.L. for Pete’s sake—to follow a molasses-voiced god? (Years before at a cocktail party at his house, Perkins had intimated to a reporter, Dave Kline of the New York Star-Ledger, that if the Alabama job ever came open, he’d be on the first plane to Tuscaloosa. After Perkins’s fourth year in New York, it was.)

His coaching rise meteoric, across just six seasons (1973-79), Perkins went from being the receivers coach at Mississippi State to the head coach of the New York Giants. Such was the life of a Bear Bryant and Don Shula pupil. At 41, Perkins was a mere babe when he took over at Alabama.

He was one of Bear’s Boys, Alabama to the bone, so he gets a pass, right? Not hardly. Forasmuch as players give to the University, Perkins will be the first to tell you it’s a different ballgame when you are installed as the coach at Alabama. Lose, and fans will quickly grow a potent amnesia as to how good a player you once were. There is an urgency of now, and all that matters is whether or not you win. But following The Man? That added another tier to Perkins’ scaffold of expectations, which he acknowledged publicly: “Nobody will ever come close to matching what this man has established. All I can hope for is that I can work in that direction.”

When Perkins took the job, the plan was for Bryant to remain as the school’s athletic director—and to stay out of football: “I will absolutely and positively not interfere,” Bryant said at his farewell press conference. “I told Ray ‘if you want something from me, you better ask for it.’”

There would be no looking over the shoulder, no puppeteering or pulling the proverbial strings. Alabama football was Ray Perkins’s show, according to Bryant.

Perkins arrived on campus on Tuesday, Jan. 4, 1983. As taciturnly as a congregation welcoming the new preacher, Alabama welcomed Bear Bryant’s successor.

For Perkins, there was little time to think or philosophize. His focus was on work, and that work was centered on the recruiting trail—“I’ll be spending very little time in the office,” Perkins told The Tuscaloosa News.

But then Bear Bryant did something no one expected.

He died.

Petal

Petal was a farming town in south Mississippi that slouched beside the larger city of Hattiesburg. Summers were cruelly hot, but young Ray Perkins cooled the oppressive heat by poaching the local fishing holes for unsuspecting bass and bream. Once he and a friend were so busy binge fishing that they accidentally dropped out of school.

Perkins fell in love with Alabama football when a guy by the name of Andy Anderson— who was a local sports legend of sorts—handed him the holy grail of college football paraphernalia: an Alabama football press guide. Like a kid admiring an old dime novel, Perkins cherished his gift and began to fantasize about playing football for Bear Bryant’s mighty Crimson Tide.

Eventually he rejoined his classmates, but work was a greater priority than school. Perkins’ confidence was built when a service station owner, Marcus James, dropped a set of keys in his hand and expected him to take care of the place. Perkins was only 16 at the time, and James’s belief in him was precisely the shot in the arm the greenhorn needed. “I’ve got goosebumps all over me just thinking about that moment,” Perkins says.

Later, in the spring of ‘61, Perkins had a brush with greatness while he was working another odd job. On Broadway Drive just outside the Choctaw Drive-In restaurant in Hattiesburg, a police cruiser pulled over a speeding motorist. Normally Perkins, star halfback of the Petal Panthers who bicycled everyday to the drive-in to work as a carhop, wouldn’t have made much of a fuss about it. After all, this wasn’t the first time a vehicle had been yanked off the road in front of the drive-in. But when Perkins cut his eyes at the driver, he noticed a familiar black, fernlike swoosh of hair. It didn’t take long for word to spread that Elvis Presley was stopped in front of the restaurant. “Everybody converged on the car,” Perkins remembered. “Yours truly included.”

But one of the fondest memories of Perkins’ young life was the day Alabama came calling. Perkins remembers “Dude” Hennessey, the Bama assistant who was assigned to him, ask, “What do you think?” Translated: Are you coming to play for Alabama?

“Well, I want to talk to Coach Bryant before I give an answer,” Perkins replied coyly.

The truth was, Perkins had made up his mind the moment Andy Anderson handed him the press guide.

Rise of a Receiver

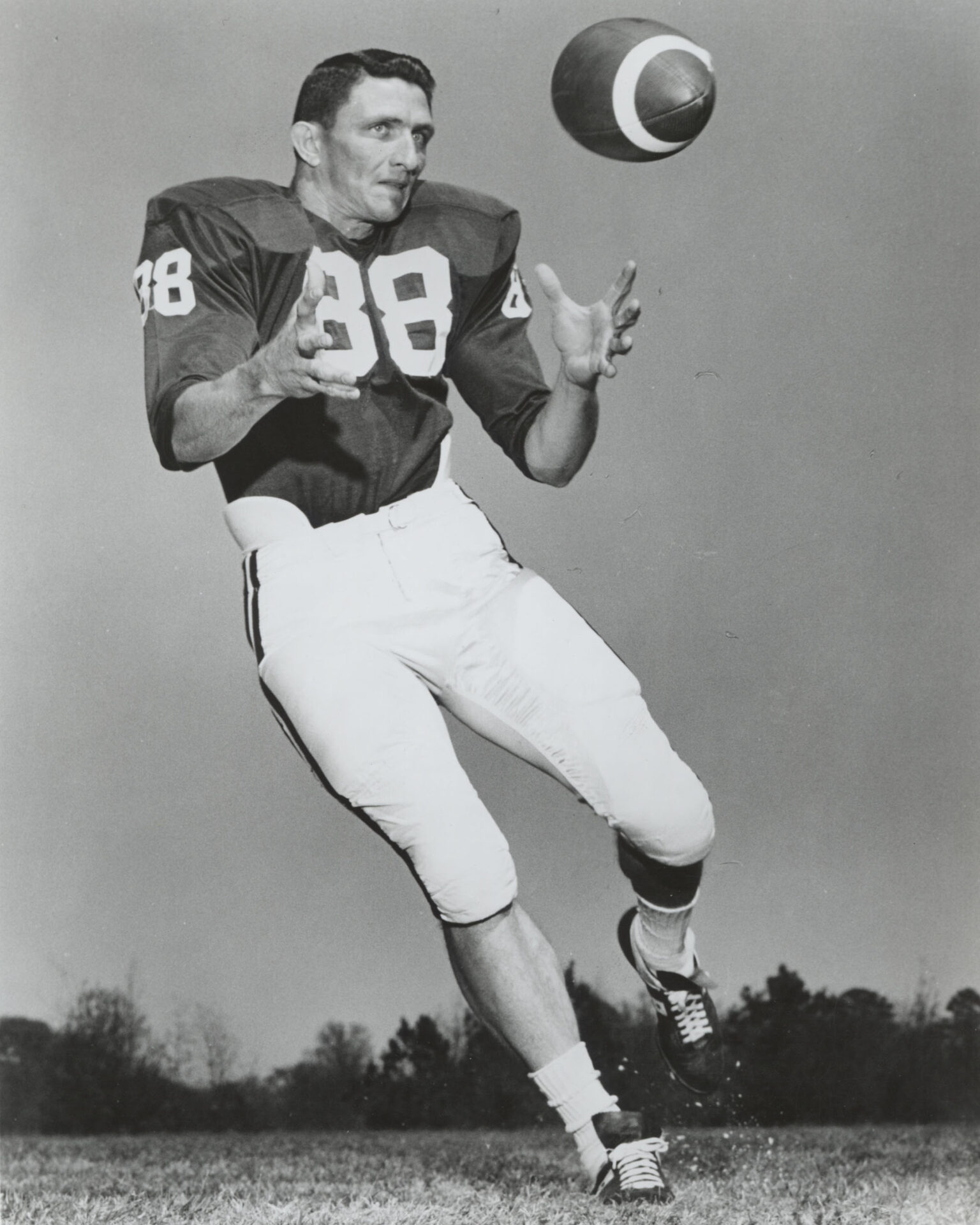

Because of Bryant and a pantheon of lesser immortals, Alabama was steeped in tradition, and Ray Perkins became a vital part of that tradition. Perkins was one of the best players on the championship teams of ’64 and ’65, and if the ’66 team had a face, it would be sculpted with Perkins’s visage.

Writer Keith Dunnavant, in his well-regarded book, The Missing Ring, described Perkins’s relationship with Alabama as such: “Imagining the 1966 Alabama team without Ray Perkins is like trying to contemplate the Super Bowl-winning Pittsburgh Steelers of the 1970s without Lynn Swann. Or the Beatles without Paul McCartney. Perkins was the face of the 1966 Crimson Tide—the personification of drive, perseverance, and mental toughness.”

A fullback-turned-receiver (after a collision with Billy Piper in practice, Perkins was hospitalized for 11 days with a blood clot on his brain, which eventually rendered him unable to risk the backfield pounding), Perkins was beloved for his grit and no-nonsense approach to the game. As the ’66 team co-captain and an All-American, Perkins was an undisputed leader of the squad who held a special bond with Bryant, due in large part to Bryant’s overarching concern for Perkins as he convalesced from the blood-clot-heard-round-the-world. “He was there everyday. All 11 days. He had to drive or get someone to drive him,” Perkins said. “That told me, he cares about me. Tons. It told me all I needed to know about him.”

There was more to like about Perkins. While distant, perhaps a bit solitary, Perkins was respected because he got everything through guts and sweat. His hands were far from supple but he taught himself how to snag a spiral. Off campus, he did not participate in the raucous shenanigans of underclassmen. He was married and lived in a converted military barracks. He avoided the temptations of beer and nightlife, his moral code ramrod-straight. And on the field, he was pure gold. Perkins once set an Orange Bowl record with nine receptions in a 39-28 win over Nebraska on Jan. 1, 1966 and then torched the Cornhuskers again the next season in the Sugar Bowl.

After his playing days at Alabama, Perkins was drafted by the NFL’s Baltimore Colts. He spent five seasons in Baltimore, catching balls from the shoulders of Johnny Unitas and Earl Morrall before retiring in 1971 to live out the life of an ex-athlete.

But Perkins had no plans of getting out of sports.

An auspicious beginning

After retiring from the Baltimore Colts, Perkins wanted to gauge whether or not Don Shula thought he would be a good coach. So Perkins asked him, flat out. “He said, ‘I think you’d like it; I think you’d do a good job,’” Perkins remembers Shula saying.

Shula didn’t have an opening on his current team, the Miami Dolphins, but had heard through the grapevine that Bob Tyler at Mississippi State was looking to fill a slot. So Perkins contacted an old friend, Tom Goode, and told him he was interested in getting into coaching. Soon Perkins was in Starkville, Miss., to commence his career—coaching receivers for the Mississippi State Bulldogs.

After only one season at MSU, Perkins was back in the bigs. An NFL scout had noticed how Perkins handled his receivers and made a notation at the bottom of his scouting form that read: ‘this first year coach, Ray Perkins, seems to be doing a good job with these receivers.’

“And that’s what Chuck Fairbanks noticed the most,” Perkins said.

Fairbanks, who became the head coach of the New England Patriots in 1973 after a six-year stint at Oklahoma, installed Perkins as his wide receivers coach that same year. From Fairbanks, Perkins learned more than the intricacies of coaching wideouts. Fairbanks was also known as a brilliant drafter. In 1973, the Patriots reached draft Valhalla, securing Alabama’s John Hannah, Darryl Stingley, Sam Cunningham, and Ray “Sugar Bear” Hamilton, a foursome that would lead them to the AFC Championship Game in 1976. “I learned a lot about drafting in New England from Chuck Fairbanks,” Perkins said. “He used his coaches better than anybody else I knew about to prepare for the draft. He would send coaches out, and they would work players out.”

After four years in Foxboro, Perkins opted for warmer weather, becoming the offensive coordinator under Tommy Prothro with the San Diego Chargers. The Chargers’ attack featured running back Lydell Mitchell and a hungry quarterback, Dan Fouts, who was fresh off a contract dispute that cost him 10 games of the ’77 season.

Perkins describes the symbiosis between himself and Fouts, one of the greatest passing quarterbacks in the history of the NFL, thusly: “If there was ever a perfect quarterback to call his own plays, it was Unitas. A close second is Fouts. In the middle of the year, it got to a point where I wanted to go see the head coach, asking if he will consider letting Fouts call his own plays. I didn’t do it, but had I stayed there as the coordinator, he would have called his own plays the next year.

“He and I thought the same,” Perkins added. “Five out of five times, the play he’s going to call is the play I’m going to call. And vice versa.”

After only one season in San Diego, Perkins began to entertain suitors for head coaching vacancies. The first was Oakland. Owner Al Davis approached Perkins about coaching the Raiders, and Perkins went so far as to fly to the Bay Area to interview. But in the end, it was Perkins’ connection to George Young that took him to New York.

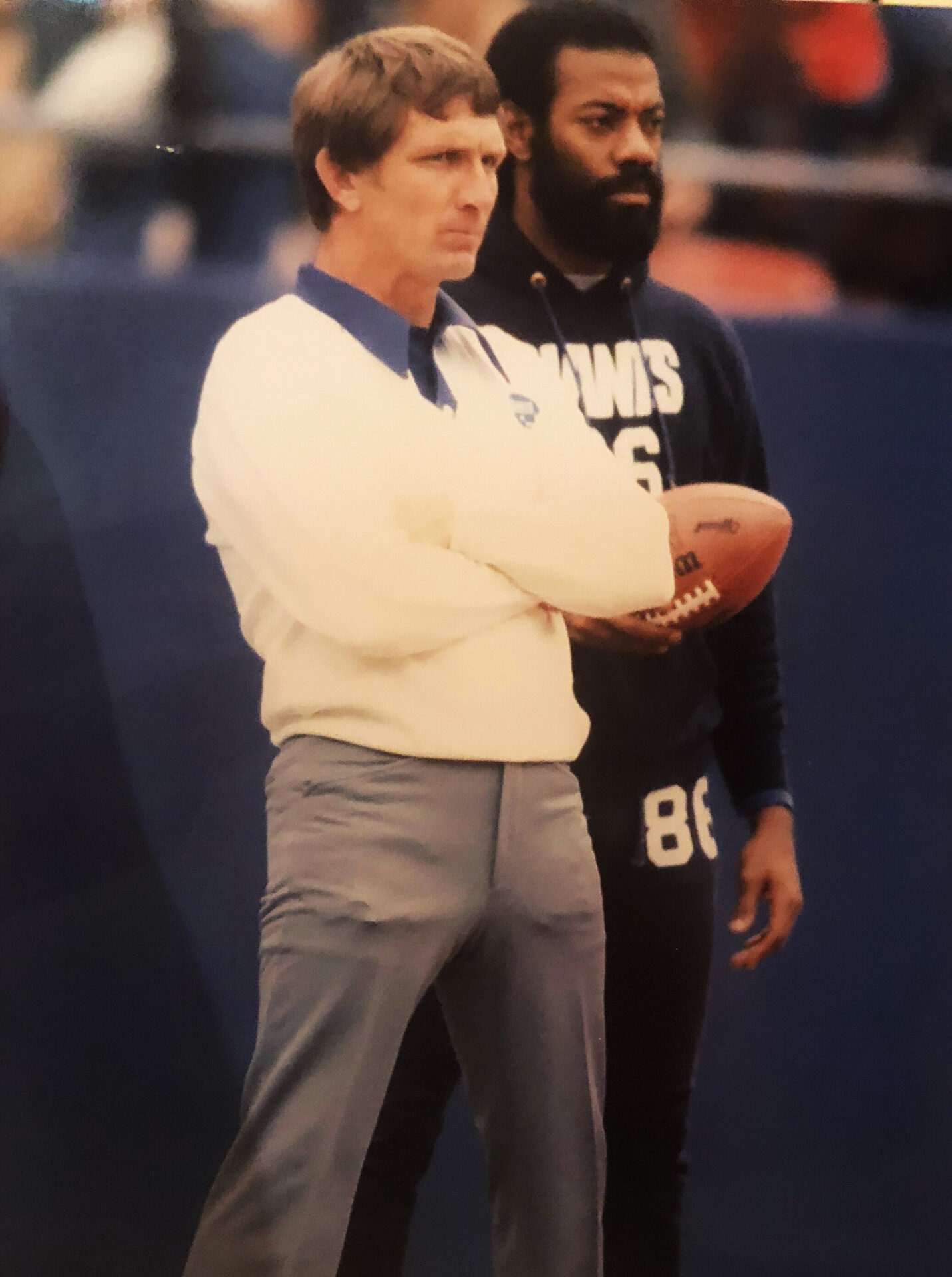

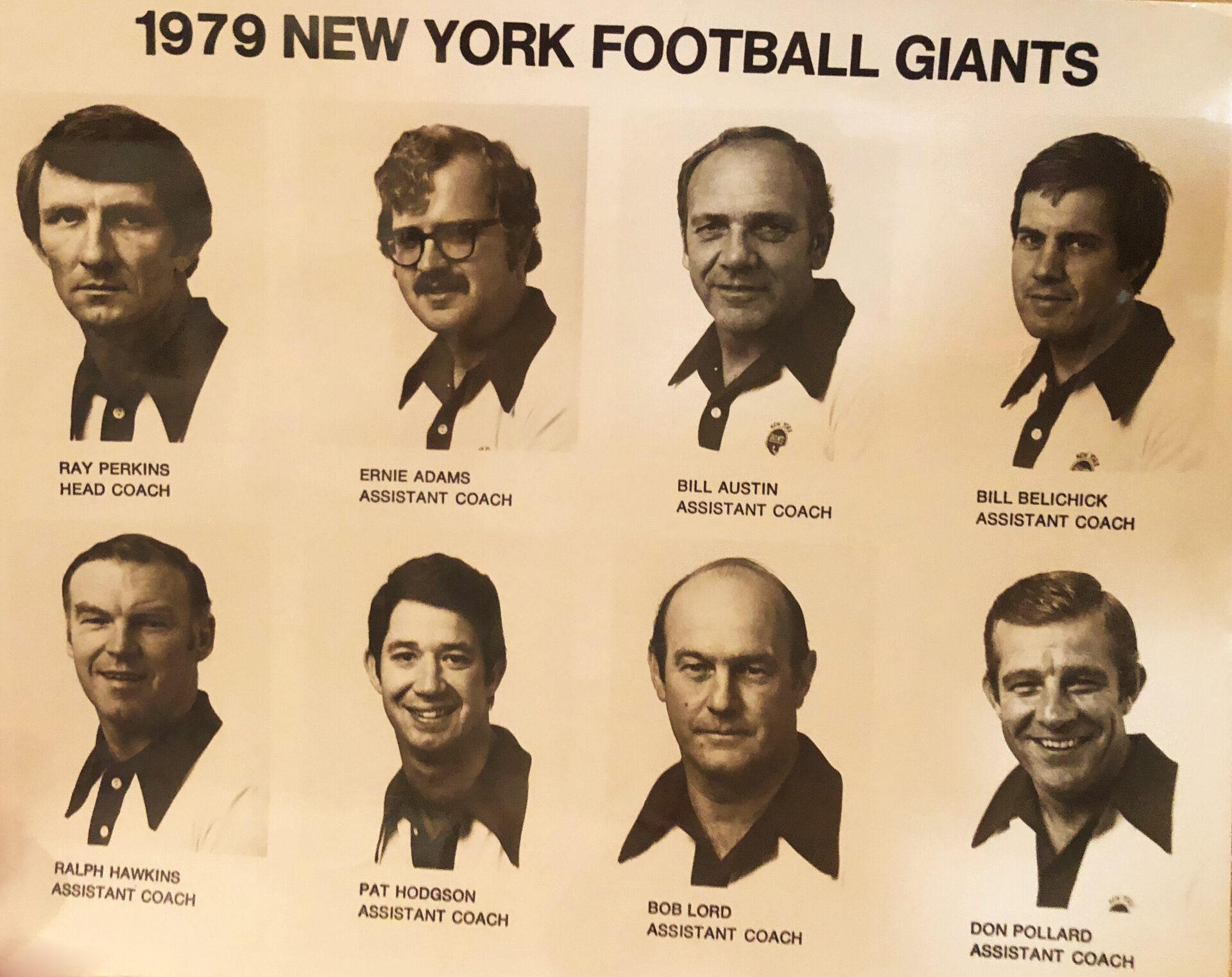

George Young had been an offensive line assistant in Baltimore for Don Shula, and knew Perkins well. So when Young, a former high school teacher and coach, was hired in 1979 by Giants’ owner Wellington Mara to become the team’s general manager, he was looking to hire a coach who could lead the team to the postseason for the first time since the early 60s. The Giants of the 1970s had become the laughingstock of the NFC, finishing last in their division on six occasions. Perkins had become a hot ticket, his star was rising and Young, impressed with Perkins’s work ethic, youthful enthusiasm, and call-it-like-you-see-it approach, hired him.

Though no one could have predicted the future impact on the Giants’ franchise, that initial winter/spring, Perkins made perhaps the greatest hiring maneuvers in NFL history and set the team on a collision course with greatness.

His first was Ernie Adams. Adams was a Harvard grad and, as Perkins describes, “ultra, ultra smart.” Perkins knew Adams from working in New England, and when Perkins left to take the job in San Diego, he promised Adams that when he became a head coach, Adams would be the first person he called. After Young brokered the deal to bring Perkins to East Rutherford, the new coach made good on his promise. As Perkins remembers, the conversation went like this:

“You on your way?” Perkins asked.

“Yep. I will be,” Adams replied.

Perkins also remembers a later conversation with Adams as he was gathering his papers and effects from his office in San Diego. “(Ernie) says, ‘I want to stick something in your ear,’” Perkins recalls. “He said I know this guy, was at Baltimore, Detroit, and Denver. He did a lot of different things for a lot of different people. Young guy. I think you ought to take a look at him.’ I said, ‘What’s his name?’ He says, ‘Bill Belichick.’”

Perkins remembered Belichick as a quality control guy, a football academic journeyman of sorts who was looking to move up the coaching totem. He didn’t know Belichick well, but trusted Adams implicitly and quickly arranged a meeting with Belichick at a hotel room in San Diego. Soon, Belichick was headed to New York.

Next Perkins dialed Steve Sloan, his old quarterback at Alabama, who was now the head coach of the Ole Miss Rebels. Perkins had a rhetorical question for Sloan: “Who is the absolute best linebackers coach out there?”

“Bill Parcells,” Sloan replied definitively.

“Where is he?”

“Air Force.”

Perkins had met Parcells while Sloan and Parcells were at Texas Tech in the mid-70s. Parcells was now a head coach and, because Perkins new Parcells’ reputation as a great defensive mind, there wasn’t much of an interview. Bill Parcells was now coming to New York.

But Perkins wasn’t done. Also that spring, Perkins embarked on what he called a “quarterback safari,” a Fairbanksesque scouring of the country for the best young field general to lead his Giants football team. He remembers an exchange he had with George Young after returning from his expedition:

“Who’d you like best?’ Young inquired.

“You’re not going to believe it,” said Perkins.

“I bet I do,” Young said. “I bet you like Phil Simms the best.”

“How’d you know?”

“I just know what you like.”

The Giants drafted Simms, the quarterback at little known Morehead State, as the seventh overall pick (Notre Dame’s Joe Montana went 82nd). Eight years later, Simms led the Giants to a 39-20 win over the Denver Broncos in Super Bowl XXI. In Super Bowl XXV, Simms, who had sustained a season-ending broken foot, watched from the sidelines as QB Jeff Hostetler led the Giants to their second Super Bowl win in team history.

In all, the four men whom Perkins brought to New York—Simms, Belichick, Parcells, and Adams—possess 14 Super Bowl rings between them. If Parcells, Simms, Adams, and Belichick were the general contractors of the Giants franchise, Perkins was the architect.

“I have a great belief in people,” Perkins says. “If I know you and I have a belief in you, that’s unwavering. I’m not a guesser.”

Even with all the coaching talent, turning the New York Giants around was like turning around an aircraft carrier. In Perkins’s first season in New York, the Giants were 6-10 and finished fourth in the NFC East, no better than the previous season under John McVay. But then the Giants went backward. Perkins’s second season, the team was 4-12 and finished fifth in the NFC East.

But by year 3, Perkins had the Giants in the playoffs for the first time since 1963. The Giants lost in the NFC Divisional Game to the San Francisco 49ers, led by Joe Montana.

In the ’81 Draft, the Giants added another piece to the puzzle, selecting University of North Carolina linebacker Lawrence Taylor as the second overall pick. Taylor had a breakout year in ’81, starting all 16 games at right outside linebacker.

In 1982, a NFL player’s strike led to an abbreviated season, and the Giants finished 4-5.

And like that, Perkins was gone.

Four Falls

The empire was under siege. In 1983, Ray Perkins walked into a SEC ecosystem with Auburn and Georgia reaching their collective peaks and Alabama having already lost its grip of dominance. Gone were the rollicking 1970s, where ‘Bama cleaved up the SEC like a fine tenderloin.

Gone was Bryant, too. And with his exodus, a power grab at Alabama commenced.

Auburn head coach Pat Dye (another Bryant understudy), was in his third season, his cupboard happily stocked with Bo Jackson, Lionel “Little Train” James, and Randy Campbell. By the time Perkins arrived, Dye and the Tigers were hitting their recruiting stride, padding their roster with future stars Yann Cowart, Brent Fullwood, and Ben Tamburello. From 1980-82, Vince Dooley’s Georgia, riding the momentum of Herschel Walker, won 33 games and lost only three, the culmination of which was a national championship in 1980. It was the greatest run in the history of Athens.

The SEC was then a 10-team league, and completing the profile of other VIPs were Tennessee, Florida, LSU, and Ole Miss. The Vols, led by Johnny Majors, were at the crest of a slow wave forward that would eventually pay dividends in the mid- to late-1980s. Firebrand Charley Pell, now in his fifth season at Florida, had already won an ACC title at Clemson and had the Gators on a similar upswing. LSU’s Bill Arnsparger was a tough former NFL assistant under Don Shula and, like Perkins, the former head coach of the NY Giants. And Ole Miss, led by Billy “Dog” Brewer, was scrappy and ever capable of upset. Not surprisingly, the bottom feeders of the SEC in 1983 were Kentucky, Mississippi State, and Vandy.

Alabama went a respectable 8-4 in Perkins’ inaugural season at the Capstone. The Tide’s only losses were at Penn State (by 6), versus #11 Tennessee (by 7), at #15 Boston College (by 7), and versus #3 Auburn (by 3). Auburn, coincidentally, enjoyed its best year in the history of its program, marching to its first 11-win season. Indeed, crimson country was gritting its teeth, as less than a year after Bear Bryant’s death, that “cow college,” left for dead in the late 1970s under the shaky tenure of Doug Barfield, had taken over as the best team in the state.

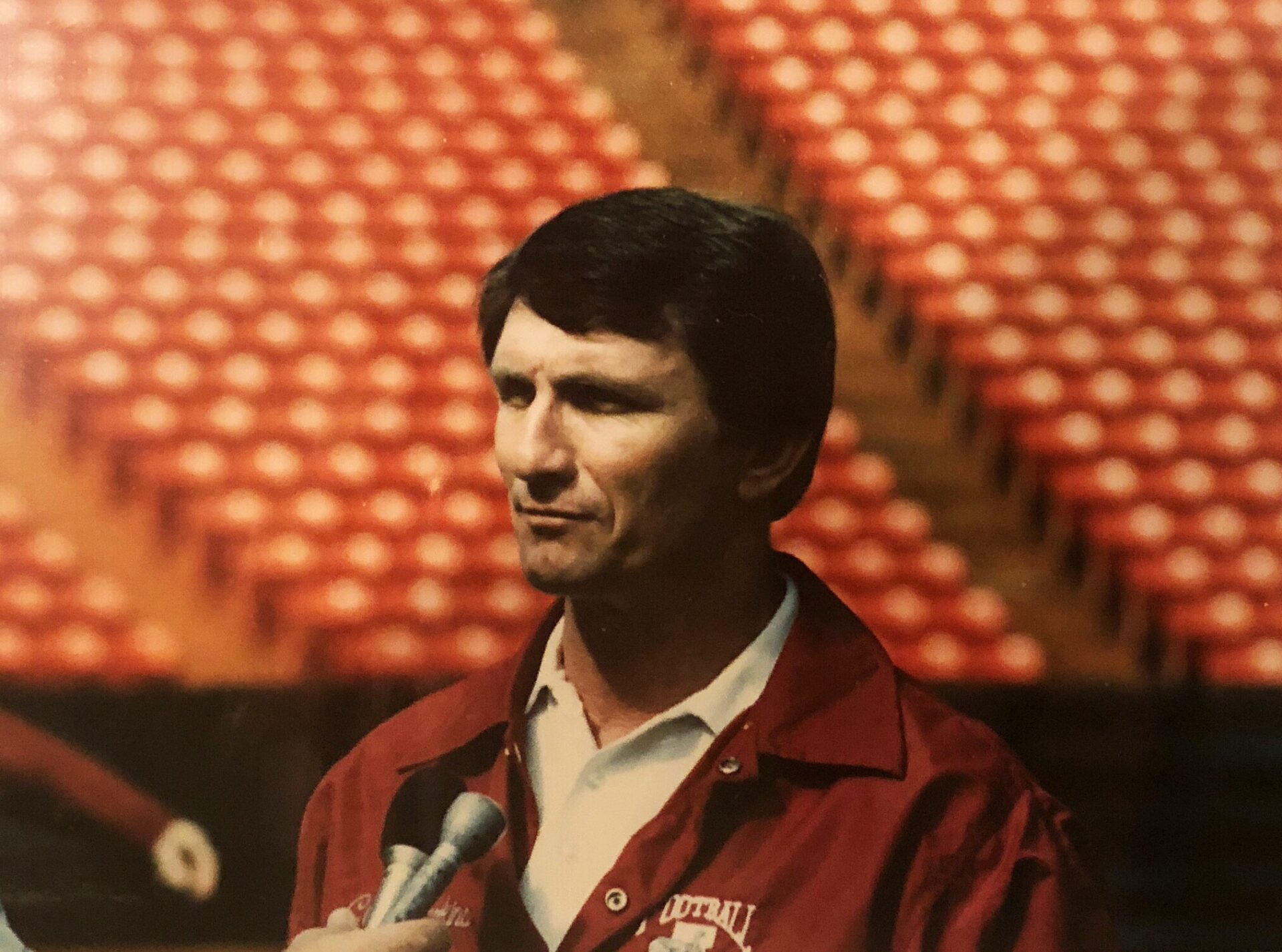

Like the dystopian novel, 1984 was an albatross year for the University of Alabama football. The first losing season since 1958 ushered raw reflections on the overall society of the program, the post-apocalyptic era minus Bryant. The season had begun with so much promise, but in the first game against Boston College, running back Kerry Goode sustained a season-ending knee injury, which set the tone for the rest of the hard, injury-laden year. On September 29, Alabama did the unspeakable: lost to Vanderbilt at home. And the world went mad.

Pressure was now coming at Perkins from all sides, as fans, boosters, and important people of Alabama expressed their intolerant distaste of losing. Press members, including a young writer for the Birmingham Post-Herald, Paul Finebaum, began to lambaste Perkins. Many felt Finebaum pulled out a verbal bazooka when he dubbed Alabama “Loserville, USA.” Further, newspaper rants, not uncommon, issued ultimatums: “He’s got to win this year, or he’s had it.”

But there were enough bright spots to salvage a shred of hope; Alabama did beat Penn State and Auburn on its journey to 5-6. A 17-15 victory (this was the “Wrong Way Bo” game) over a vastly talented Auburn team was a signal of the team’s undying spirit.

Still Walter Lewis, the former ‘Bama quarterback who was then with the Memphis Showboats of the USFL, expressed his sympathy for Perkins: “I think about the hell Coach Perkins must be going through. I asked him the other day how he stands up to all the pressure from the alumni and all that. And he said, ‘It comes with the territory. The way things are, you’re either the sheep or the goat. There’s no real in between.'”

After Bryant died, Perkins took over his duties as athletic director, and embarked on an ambitious (and much-needed) construction agenda that included renovations to Bryant-Denny Stadium, Memorial Coliseum, and the building of a new administrative facility and practice facility. But the press seemed to hone in on two things: the care by which Perkins handled the vestiges of Bryant, and winning and losing.

Besides the losing, Perkins came in and un-Bryanted several things: redecorated the grubby athletic dorm (replacing the archaic wallpaper, adding swanky new furniture), switched from Golden Flake to Frito Lay, and scrapped Bear’s beloved wishbone offense. But what really burned the Bryant loyalists was Perkins’ decision to take down Bryant’s tower—the citadel shrine that overlooked the practice field for decades. Some folks in Alabama swore the world split into when Bryant went to Calvary. They set their calendars by Bryant’s death, like B.C. and A.D. And when Perkins took down the tower, it was like pulling down a hero’s monument.

What rubbed Alabama the wrong way was not that Perkins had the audacity to run his own show (Bear demanded the same thing when he arrived in 1958) it was the way Perkins went about changing the guard. Alabama fans perceived Perkins as remote and unfeeling as he embodied a Sinatralike “My Way” attitude toward steering the gloried Alabama football program. Fans were still getting used to the fact that Bryant was not the coach and they perceived Perkins to be icy and bullheaded. The old was gone, the new was here, and Perkins was burdened with memorializing Bryant properly and moving Alabama football forward into a new era without him. Sure, venerating Bryant had its proper place in museums—such as the one constructed in 1985 to preserve Bryant’s legacy—and otherwise, but many Alabama fans expected Perkins to pick up right where Bryant left off, and not change a thing. Unfortunately, that didn’t happen.

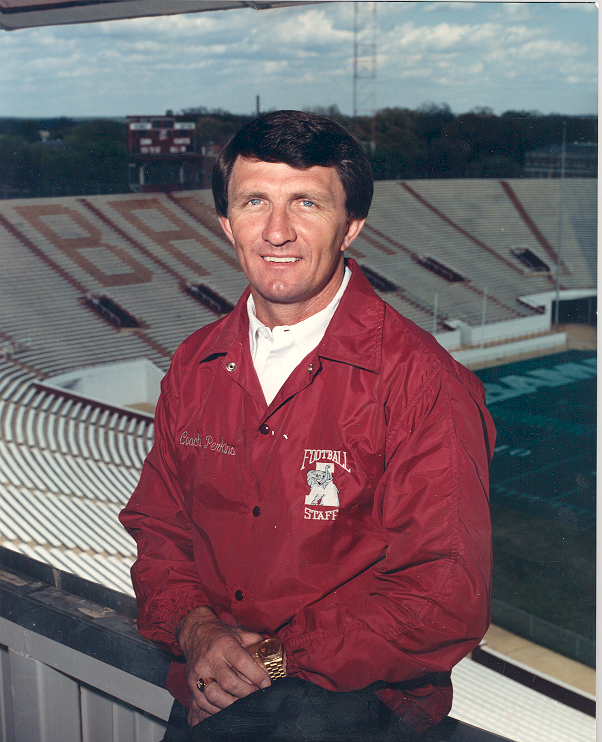

There were a few tough decisions, such as aforementioned tower, that caused the fan base to question Perkins’s judgment, but overall the Alabama faithful knew that Bear had tabbed a fighter. It wasn’t merely that there was a new leader making new decisions about old ways. Perkins stood at the divide between two eras. One foot was in the Renaissance, while the other was in the Age of Reason. Perkins was charged with leading the Crimson Tide into a new promised land, but often he came off stiff, lacking a natural salesman gene. His neat hive of hair, his windbreakers, his youthful face, his glacial eyes all seemed to contrast the severer but savvy Bryant. Simply put, he wasn’t Bear.

“They won’t accept him no matter what he does,” Walter Lewis said. “Maybe it’s gonna take time, but people down here, they might need forever.”

If Perkins was perceived a certain way by the press and the public, many of his former players held a different opinion. They spoke highly of their coach and enjoyed playing for him. “We had a great relationship from Day 1,” said Kerry Goode. “I signed as a defensive back, and the first week, I went and sat in his office and told him I wanted to play running back…and he gave me a chance. I think some of the older guys that had been around Coach Bryant had a difficult time adjusting. You’ve got a head coach now that was getting in your face. For me, it was great. I had no problem with him.”

Tommy Cole, who played defensive tackle from 1985-88, said, “He was a great coach and you definitely knew where you stood with him. The players loved him and we respected him very much.”

Perkins quelled many of his critics by righting the ship in 1985, producing a 9-2-1 campaign punctuated by Cornelius Bennett’s and Jon Hand’s strong defense and Van Tiffin’s toe. Tiffin’s heroics—a 52-yard game winner in the 1985 Iron Bowl—gave Perkins his second consecutive win over Auburn, a 25-23 victory at Legion Field in Birmingham. On the year, Alabama defeated Georgia, Texas A&M, Auburn, and USC in the Sun Bowl—not bad, considering 1984. And even though Tennessee had captured the SEC Title and there was a pileup for first place, it seemed as though Alabama was out-muscling Auburn as the South’s No. 2 team.

That set up 1986. The year began with a meeting with No. 9 Ohio State in the Chase Kickoff Classic in Perkins’s old stomping grounds, the Meadowlands in East Rutherford, N.J. Ohio State, coached by Earle Bruce, featured receiver Cris Carter and linebacker Chris Spielman. Bama won, 16-10.

Behind the arm of Mike Shula, the legs of Gene Jelks and Bobby Humphrey, and a stalwart defense led by Derrick Thomas and Bennett, the Tide then reeled off six straight victories, including the program’s first-ever win over Notre Dame, to stand at 7-0. Bennett’s crushing sack of Irish quarterback Steve Beuerlein inspired an oil on canvas by artist Daniel Moore. A 56-28 win in Knoxville ended a four-game orange jinx, and Alabama appeared to be in a position to make a run at…something.

But after the Tennessee game, the wheels flew off. Alabama got hit in the mouth by an angry Penn State in a 23-3 home loss. In November, ‘Bama lost nail biters against LSU and Auburn—games that should have been won. The Tide finished the year with a 28-6 Sun Bowl win over Washington.

Then Perkins surprised everyone by accepting the head-coaching job with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers for $750,000 per year. “I do so with mixed emotions,” Perkins told the press. “Alabama has progressed leaps and bounds in the last four years.”

“We hated to see him go to Tampa Bay,” said Tommy Cole.

Reflecting on his decision to take the Bucs’ job, Perkins said, “I had a good offer from Tampa Bay, one of the best offers any coach had had until that point. So, when I weighed everything against everything—the job here, job there, guaranteed money, not guaranteed money—you know, this job (in Tuscaloosa) hasn’t always been a $15 million dollar a year job.”

In four falls, Perkins’s overall record at Alabama was 32-15-1 (a 14-9 conference record).

Summer, 2018

On a sunny June day, Ray Perkins lurches up the outside stairs and through the glassy entrance of Bryant-Denny Stadium in Tuscaloosa. It’s been 32 years since Perkins resigned as Alabama’s head coach to take the Tampa Bay Bucs job, but today he is welcomed with open arms.

At Alabama, coaching royalty doesn’t require an I.D.

Perkins looks sharp in his crimson sport jacket and slip-on loafers. His haircut—a short, Caesarlike presentation—resembles his playing days more than his coaching days, and his eyes have not lost their cornflower blaze. At 76, Perkins is seven years older than Bryant ever was.

If there was ever any animosity between Perkins and Alabama, all seems to be forgiven. Now there are no towers to move, no controversial decisions to make, no probing questions regarding losses to LSU.

A month earlier, Perkins and his family moved back to Tuscaloosa from a 17-year stretch in Hattiesburg. Perkins says there were several reasons for the move. First, he has easier access to his heart doctor in Birmingham. Second, his daughter, Rachael, who is on the Bear Bryant Scholarship, recently took a job working as a recruiting student assistant for Coach Nick Saban. And third, Perkins has land in north Tuscaloosa County he once purchased with his signing bonus.

Perkins says he feels at home in Tuscaloosa, and as he drives down Bryant Drive he thinks mostly about the benefits provided to him by being a part of the University. “This is my school. I love the people. This is home, for me. When I was 14 years old and I first heard of the University of Alabama—since then, it’s been what I’ve thought about as home,” Perkins reflects. “I tell you what comes to mind, more than anything, just what this place did for me. That’s a little bit selfish. It gave me opportunities that I, quite frankly, would not have had anywhere else. We cashed in on some of those opportunities— a few we didn’t—but it was yes more than no.”

After greeting a few staff members at the stadium, Perkins takes an elevator to the fifth floor. The doors open, and he walks over to an inside platform overlooking the interior of the stadium. For a moment, he gazes off through the glass that separates him from the field he used to patrol, so long ago, as the head coach. Sure, Perkins is considering the immense nature of the place, but he’s also contemplating history. He breaks the silence by running his hand through the sky to demonstrate the improvements to this coliseum in the last half-century. Below his feet lies the bowl once known as simply Denny Stadium—the venue Perkins first saw when he arrived on campus as an Alabama player in 1964. About eye-level are the rows of stadium boxes on either side of the field, and above, the upper deck encircles this vast and uncompromising facility.

Later, when Perkins retreats to a lower floor, he pauses to gawk at a lighted display of championship rings depicted in a stairwell. His mind hunts for the championship rings that bear the inscriptions “1964” and “1965.” He probably thinks there is a ring missing.

Then Perkins walks through the corridor and into the Alabama locker room, where his name and number hang on a placard above a locker. He shares his spot with O.J. Howard, a player who also wore No. 88. Howard is a current player for, ironically, the Tampa Bay Bucs.

As he walks though the stadium, Perkins shares anecdotes of Bear Bryant and Joe Namath, legends he knew. He isn’t too nostalgic about what was or even what might have been, had he stayed longer than four years at Alabama. He isn’t haunted by blissful hypotheticals that could have ushered a better life. As a matter of principle, Perkins takes things as they are, and leaves things where they end. Could he have had more success at Alabama? He says he doesn’t think about it. What’s the use? It’s not what happened.

“I don’t regret anything about it,” Perkins says. “It didn’t work for me, ok? And I know why, but that’s going to stay with me because I’m not into hurting other people. But for what’s happening now, it had to go through a certain stages, you know. Looking back on it, I think it was good that I left. I think it helped people make decisions, help people realize what decisions need to be made by whom.”

Perkins sees his time at Alabama as a bridge to what’s happening now.

When his tour is over, Perkins walks through the iron gates of the stadium and gets in the car. I know Perkins has some hard bark on him, so I’m cautious when I ask him about his decision to remove Bear’s tower that once overlooked the practice field. Whether or not it was symbolic of the changing of the guard, still to this day, Perkins remains adamant in his belief that the tower should be enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. “I took the tower down to ship it to Ohio, where it should be,” Perkins said. “I made a couple of calls, and they were tickled to death to think they were going to have Coach Bryant’s tower in Canton, Ohio. And I still feel strongly it should be in Canton, Ohio, not in Tuscaloosa, Ala. Now, you are going to have a lot of people that don’t agree with that, I imagine, because of where it is.”

There’s one more reason why Perkins has come back to Tuscaloosa—to give back to the University in any way he can. “It makes it a lot more convenient to go to things I can support…whether it be personal or financial, whatnot,” Perkins said. “I’ll be involved as much as people would like me to be involved in whatever, but I’m not going to go out and hustle.”

Perkins misses coaching, and is truly thankful for all of the people along the way who have contributed to his life. Now he hopes in his final years, he can do some good.

“We’re coaching somebody every day,” Perkins says. “It’s either good or maybe not so good. But it’s still something. I would hope and pray that it’s good.

“All I want to do is, if I could in some way, shape, form, or fashion, help another human being, another person on the road to success in football or anything else, I’ll be the first in line to do that.”

Coaches always seem to settle in the place they feel the most loved.

And so, as Ray Perkins turns the page to this latter chapter of his life, you get the sense that something new is beginning, more so than something is coming to an end. H&A

Follow Hall & Arena on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.