Recent Features

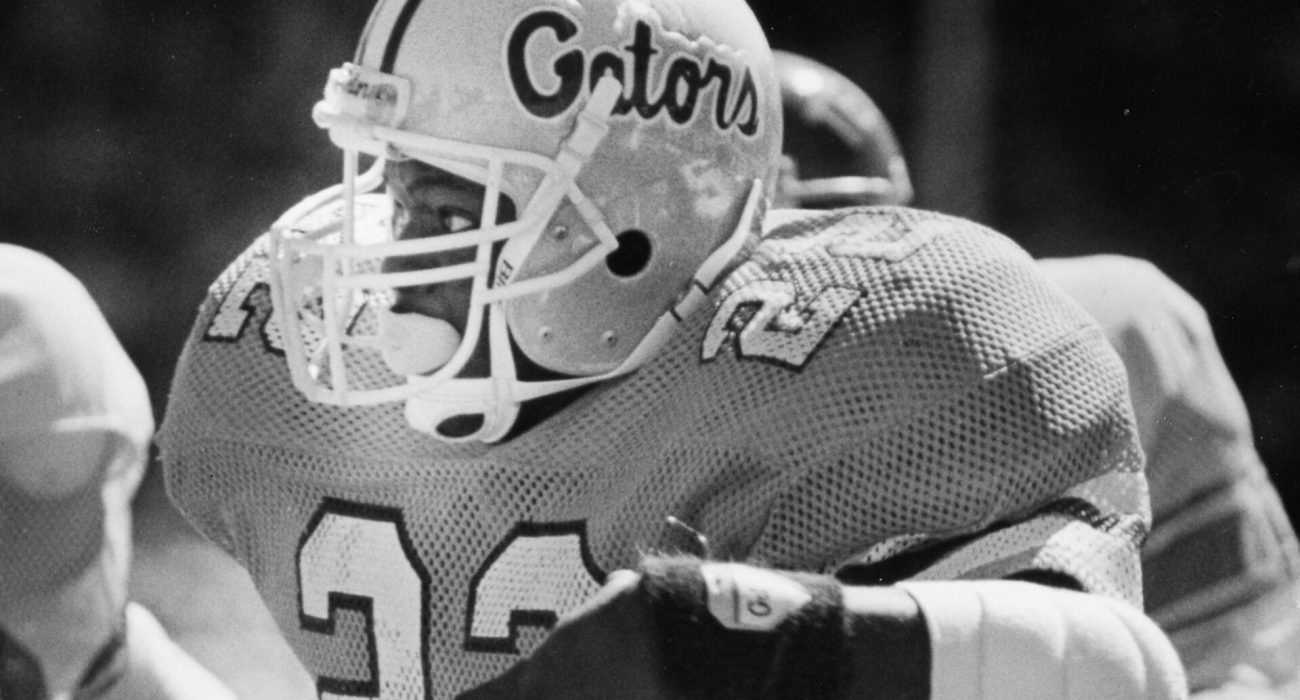

The Day Emmitt Smith Ran All Over Alabama

Subtle is not normally a word used to describe Emmitt Smith’s career. There was nothing subtle about his career with the Dallas Cowboys, one that produced the glimmer of three Super Bowl rings and eight Pro Bowls. There was nothing […]

Continue reading this article and more from top writers, for only $9.99/mo.

Already a TALEGATE Subscriber? Log in here.

The Talegate Podcast: Interview with 2025 Miss Softball Ambrey Taylor

June 14, 2025

No Comments

Did you know that the Alabama Sports Writers’ Association recently named Curry senior softball player Ambrey Taylor the 2025 Miss Softball for the state of …