The papers offered no mercy. The Times-News out of Hendersonville, North Carolina, ran the story, cobbled together by the Associated Press: “Bill Battle Resigns As Tennessee Coach.”

On November 22, 1976, when Bill Battle met his professional nadir, he was thirty-four years old, made $48,000 per year, and had been the coach at Tennessee for seven seasons. When he was hired in 1970, he became the youngest head coach in the country at twenty-eight years of age. In his first three seasons, he went 11-1, 10-2, and 10-2, and seemed well on his way to making Tennessee a consistent Southeastern Conference (SEC) powerhouse.

Now, at thirty-four, resigning on his own accord after a string of pedestrian campaigns, Battle faced retirement.

“In like a lion, out like a lamb,” the story in The Times-News read.

Still a young man, Battle faced the prospect of never coaching again. He was fatigued, the multifaceted duties of coaching siphoning out all his energy. Indeed, football had been the centerpiece of his life since he first knotted up his cleats for the neighborhood games of West End, Alabama. But now, The Battle Plan was uncertain.

Thirteen years earlier, Battle walked into Bear Bryant’s office and told him he wanted to be a coach. Back up. You didn’t just walk into Bear Bryant’s office, but on this day, Battle could show cause: as President of the A-Club, he wanted to talk to Bryant about planning the annual A-Club party later that spring. (A-Club was a distinguished honorarium for players who lettered at Alabama. Selection of varsity letters for A-Club was purely subjective: Bryant told you whether you made it.)

After a few minutes of party planning, Bryant, beneath several Chesterfields, began to inquire about Battle’s future.

“What do you want to do?” Bryant asked.

“I want to be a coach,” Battle replied.

“Well, don’t go into coaching until you can’t live without it.”

“Yes sir.”

“But I tell you one thing,” Bryant added, “Bobby Drake Keith and Gene Stallings are making $10,000 a year, and not many people anywhere are making that much.”

Battle smiled. The thought of ten thousand dollars was a lot for a young, green, rawboned kid who once collected quarters on a paper route.

“My goal was, if I can make $10,000 a year, I’ll be set for life,” Battle once reflected, relaxing in an upholstered chair in his roomy Athletic Director’s office overlooking The University of Alabama practice field—the same one on which he used to slog unceasingly.

The grand irony of it all was that when Battle was Athletic Director at Alabama, he had a salary north of $600,000, making more than $10,000 per week.

After graduating from Alabama in 1963, Battle was hired as a graduate assistant for Bud Wilkinson at the University of Oklahoma. At the end of his playing career, Battle had surmised that the Alabama coaching staff had gotten to know him about as well as they could, and it would be a good career move to gain exposure to another program and another big-time head football coach. Battle was also intrigued with Wilkinson’s involvement with President Kennedy’s Council on Youth Physical Fitness Program, of which Wilkinson was chair. So, Battle penned a letter to the Oklahoma icon before the start of the 1962 season, asking if he could use some help.

“As fate would have it,” Battle said, “Alabama played Oklahoma in the Orange Bowl at the end of the season. After our game, which we won 17-0, Coach Bryant introduced me to Coach Wilkinson. He told me he had received my letter and would be pleased to have me join the Oklahoma staff as a graduate assistant.”

Battle coached the freshman ends and bestowed his knowledge of Bryant’s option attack on the coaching contingent in Norman.

“Coach Wilkinson coached the backs in individual drills every day and he had me join them, as I knew how to play against the option. I’d play the end against the quarterback and hold the dummy. If they were doing a read off the fullback option, I’d go one way and make them go the other way. On the QB option I’d make the QB either pitch or keep,” Battle said.

Both Wilkinson and Bryant had the same goal—winning—but approached that end with different methodologies. Both men coached their personalities and hired around their weaknesses, and Battle was able to witness firsthand the stark contrasts that funneled to the same result: winning on the football field. These early experiences were invaluable to Battle’s resume, for in two quick, chess-like moves—playing at Alabama and coaching at Oklahoma—Battle’s branch would extend from the coaching tree of two of the strongest oaks in the history of college gridiron soil.

Before Battle could achieve the full measure of education on these matters, though, two critical events occurred: Wilkinson retired from football to run for the U.S. Senate and President John F. Kennedy was shot in Dallas. Over the course of a year, Battle had received a commission in the U.S. Army as an advanced ROTC graduate, and was assigned to the Army Athletic Association as a second lieutenant. He parlayed his experience at Oklahoma and subsequent military accommodation into an assistant coaching job at the United States Military Academy in West Point, NY, for coach Paul Dietzel.

“Coach Dietzel had won a national championship at LSU in 1958 with Billy Cannon, an All-American running back, and his Chinese Bandit defense. He shocked the world by leaving LSU in 1962 to go to West Point, where he had coached earlier in his career,” Battle said.

Battle spent two years at West Point in 1964 as plebe defensive coordinator, and in 1965 as varsity receivers coach.

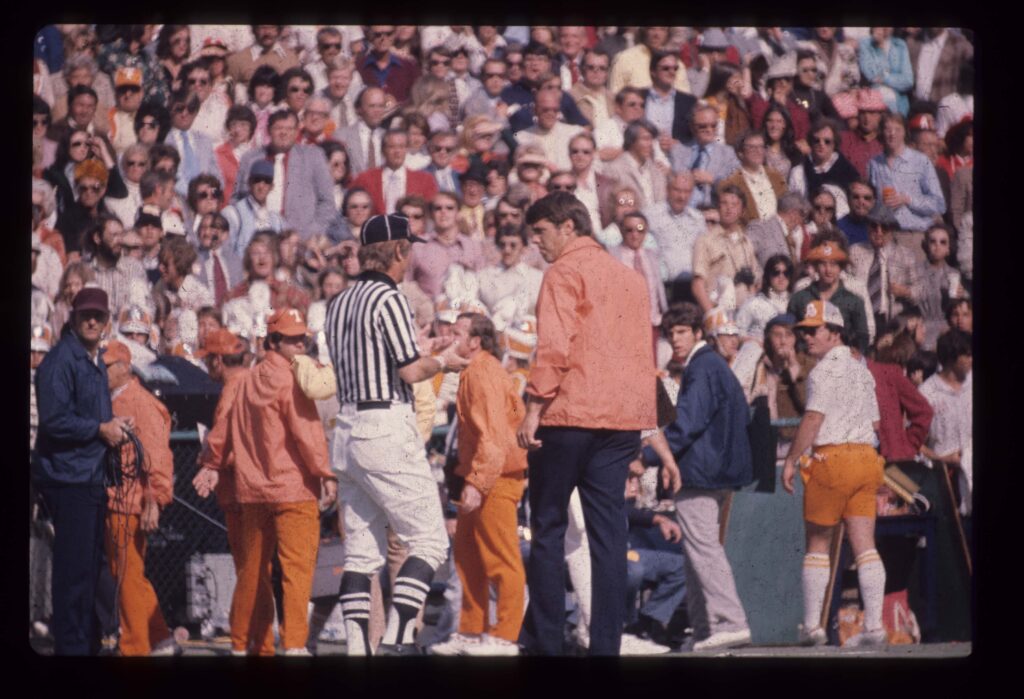

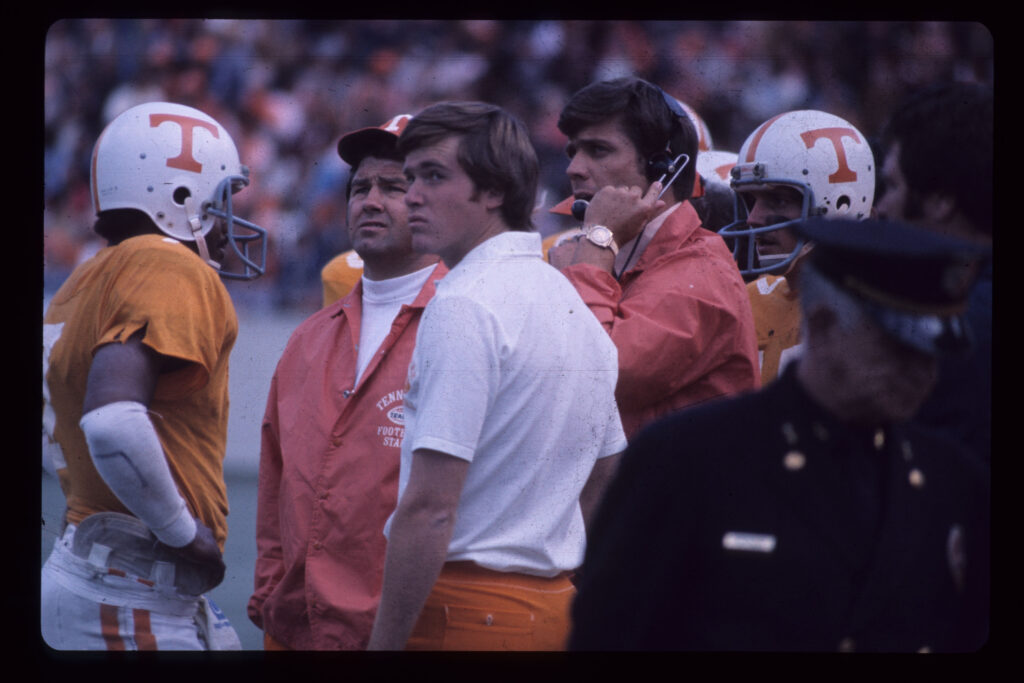

In 1966, he joined the staff at Tennessee, where he shadowed head coach Doug Dickey, a Vermillion, South Dakota, native and former Florida player who then patrolled the Knoxville sidelines. Battle served as assistant coach in charge of receivers. Three years later, after Dickey’s exodus to his alma mater, Battle assumed duties as head coach of the Volunteers at only twenty-eight years of age.

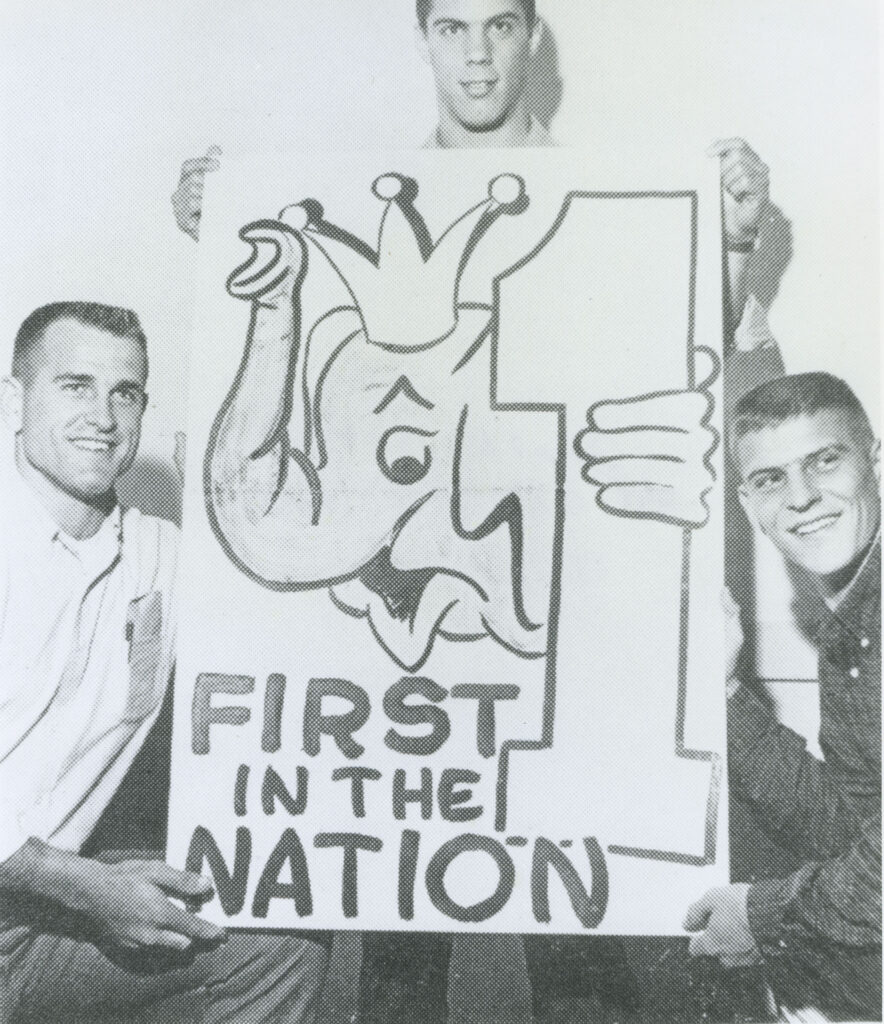

Building on the program that Dickey established, Battle found immediate success and defeated three of his former coaches in one fell swoop. On course to an 11-1 season in 1970, Tennessee trounced Air Force, Army, Florida (Dickey’s new team), Georgia Tech, and Alabama at Neyland Stadium in Knoxville, 24-0.

In only seven years, the pupil had gotten the best of the teacher.

Tennessee’s lone loss that year was administered by Auburn, a 36-23 defeat at Legion Field in Birmingham. Later, three of Battle’s players were drafted by NFL teams: Lester McClain (Bears), Bobby Scott (Saints), and Chip Kell (Chargers).

After back-to-back 10-2 campaigns in ’71 and ’72, Battle could claim victories over a proverbial Mt. Rushmore of coaching: Bear Bryant, Joe Paterno, Vince Dooley, and Frank Broyles. Battle snagged two wins over Penn State and Joe Paterno (Dec. 4, 1971, and Sept. 16, 1972), defeated Broyle’s porkers from Arkansas in the Liberty Bowl on December 20, 1971, and bested Dooley’s Dawgs on November 4, 1972.

In addition, the Volunteers defeated Bud Carson—who would later go on to fame with the Pittsburgh Steelers— Pepper Rogers (Georgia Tech), Shug Jordan (Auburn), Hayden Fry (SMU), Jerry Claiborne (Maryland), Paul Dietzel (the new South Carolina coach) and Charlie McClendon (LSU).

But a slow descent began in 1973, when Tennessee went 8-4, the losing end of the ledger frustrated by tight ballgames that somehow slithered out of Battle’s grip. Trending downward, that year was followed by 7-3-2, 7-5, and 6-5 seasons. Battle promised forebodingly after the 1975 season that “nobody will have to ask me to resign” when it was time to make a coaching change, and after losing to Kentucky in the fall of ’76, he made good on that promise.

Reflectively, Battle looks back on his years at Tennessee with fondness. It is not the win-loss record that matters now; indeed the scores can only be recalled by a select few. Rather, Battle’s influence on the players’ lives is the thing that truly endures.

“[Tennessee] was great,” he says. “Looking back, I wouldn’t change a thing. I’d change the way it ended, but I have great feelings for the University of Tennessee. Tennessee changed my life in a positive way, and I hope I had a positive influence on the players. Those are the things that are meaningful.”

Battle finished with a 59-22-2 across seven seasons as Tennessee’s head coach.

The Business World

After stepping away from the coaching arena, Battle, his whole life in front of him, looked for a fresh start. Myopic in his worldview, Battle wanted to see how other people lived, and because of that, he needed to step back and look at the universe from thirty-thousand feet.

“I was committed to taking a year off,” he said. “I was committed to seeing what the business world was like. Of course, whenever you change professions, in many ways you are taking a step back, but it was challenging and exciting in some ways.”

In 1977, he went to work for a construction materials company based out of Selma, Alabama—a company, he believed, had great potential. In this move, Battle already had a degree of familiarity: his employer, Larry Striplin (who now has his name etched on the side of a building on the campus of Birmingham-Southern College), was Battle’s Little League football coach. Coach Bryant, of course, was on the board of the company (he had been slipping off inauspiciously to attend board meetings for a number of years) and advised Battle that this might be a unique opportunity.

It followed that Bryant couldn’t have been more right. Over the next six years, company revenue increased five-fold, from $12 million to $60 million in sales. “The growth was fueled by a great sales job that Larry [Striplin] and team did to sell a job in Tabuk, Saudi Arabia,” Battle said. “I learned a lot about business during those years, both in things to do, and especially in things not to do. I moved up to president of the window company, our largest company, in three years.”

A year after Battle moved to Selma, he began to entertain thoughts of getting back into coaching. A job came open and Battle thought if it’s meant for me to be back in coaching, they’ll call. The athletic director at the school phoned later that night. After an hour on the phone, Battle huddled his family together and asked for their opinions. His young kids said ‘go for it!’” His wife said, ‘whatever you want to do.’”

This assent led Battle to an airplane and later a dinner with the president of the school. The athletic director, like Battle, was a young guy, driven, and the pair shared a conversation until 1 o’clock in the morning.

But something just wasn’t right – “I made him nervous, and he made me nervous,” Battle recalls.

The next day, he visited with the Board of Trustees. On the flight home, Battle felt restless about the potential opportunity. He had knots in his stomach. At a layover in Atlanta, he perused the magazine store and picked up a copy of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, a paper that had, a decade earlier, excoriated one of his teammates and his head coach. As Battle scanned the pages, he read “Pepper Rodgers under fire at Georgia Tech” and “St. Louis Cardinals coach locked out of his office” and he thought to himself, why would I want to do this again?

The next morning, he phoned the school and told them to take his name out of the hat (though he doubts whether, at that point, the school still had interest in him).

Bolting the proverbial door on the coaching profession, Battle accepted his fate and new calling as a businessman. What he didn’t realize at the time was that he was perfectly poised to begin a commercial enterprise that was the perfect marriage of his business skills and athletic expertise, one that would later become one of the most successful businesses in the history of college athletics.

Meanwhile, a local golf putter company, Otey Chrisman Manufacturing, was gobbled up by Striplin’s soaring outfit, and as luck had it, the newly installed manager of that company understood the licensing business. Battle soon became an apt understudy. The company acquired licenses with golfer Jack Nicklaus for Golden Bear golf gloves, socks, and accessories, which they sold to golf pro shops, and for Golden Bear eyewear sold to the ophthalmic trade.

“It was a fascinating business,” Battle said, “and divine intervention.”

The company also acquired licensing rights from Disney for children’s eyewear and Chris Evert Lloyd from IMG for ladies’ eyewear.

Licensing was a relatively new concept at the time. In Battle’s playing days, the only product using the Alabama logo was a decal that read “Alabama #1” (with Denny Chimes serving as the #1), and even though the NFL and Disney led the way in terms of licensing their brands, their efforts were only nascent at the time. Battle looked at the NFL model and realized that the same centralized effort could work on the collegiate level, and his experience with Nicklaus, Disney, and IMG gave him the experience to see it through. He surmised that the same branding and licensing campaign could work for his old ball coach, but, more broadly, that college programs would see the benefit of protecting their brand.

Bryant intimated to Battle that he had been represented by IMG, one of the best sports marketing companies in the world, but was thinking about changing agents. Battle, shocked that Bryant even had an agent (thinking he focused on football 24/7) approached his old coach with a unique business opportunity.

“I thought we might do for Coach Bryant what Golden Bear did for Jack Nicklaus,” Battle said.

Bryant initially rebuffed self-importance. “I told Coach Bryant about our company and he said, ‘Aw I ain’t got nothing to sell, the best in the business have tried to sell me for years…all I want is someone to take my requests for speaking engagements and tell ‘em I can’t come,’” Battle said.

Battle realized that bagging the Crimson Bear would take a bit more persuasion and cerebral acuity. But after a bit of coaxing, Bryant eventually signed an exclusive agency agreement in 1981 with Battle’s company to allow the manufacturing of products using his name and likeness.

Timing could not have been more peerless and unfortunate. On the one hand, landing Bryant eventually led to the procurement of licensing rights to the entire university, an effort to which Battle was put in charge. The downside was that Bear Bryant died on January 29, 1983, and the possibilities with his brand were short-lived.

Still splitting his time between the licensing and window business, Battle eventually saw an opportunity he could not pass up and bought out the licensing division of Striplin’s enterprise in 1983. Though Selma was a fine town, Battle concluded that the city of Atlanta offered the transportation access that would be required to accommodate such a wide-spanning business, and moved his upstart company to the Georgia capital in 1984.

His initial goal was fifty schools, and one of the first steps in the process was to contact the Southeastern Conference. “I’d like to represent all of the schools,” Battle told the conference powers-that-be.

Instead of opening him up to the Land of Oz, all Battle received was rights to protect the SEC logo.

He soon realized that this was going to be a school-by-school adventure and began setting up appointments with Southern universities as well as those along the eastern seaboard. To acquire accounts, Battle made a brilliant tactical move. Since his venture was more about the Xs and Os of money than it was about athletics, he began to meet with college vice-presidents—campus experts in business—instead of employees in the athletic department.

Initially, the erudite minds did not think there was revenue to be had, and so Battle had to employ a bit mathematics into his sales pitch. He showed them that if each university set up a licensing program of its own, a payroll expenditure of at least $40,000 per year would be required. His company, on the other hand, could represent the university for a whole lot less and offer comprehensive services in marketing, enforcement, and brand protection. These turned out to be numbers the colleges simply could not pass up.

Soon, Battle’s company had the licensing rights to nine schools, seven in the ACC and two in the SEC (Alabama and Ole Miss) and was chasing down more. Battle’s first licensing check to Alabama was in the amount of $400 and the company grew astronomically from that point.

Since founding, Collegiate Licensing Company, whose motto is “Connecting Passionate Fans to College Brands,” created billions of dollars in new revenue to their collegiate partners, now totaling over two hundred accounts. So anytime a fan buys a college T-shirt on Amazon or at the local five-and-dime for one of these partners, the school has Bill Battle to thank.

West End Story

Bill Battle’s work ethic and business chops can be traced back to his early days in West End, Alabama, where the pop-up sandlot games at Woodward Park in the 1950s were the stuff of legend. There was a swimming hole and tennis courts, a baseball diamond and football field, and this is where young Billy Battle learned to play ball.

“We had games of all sports,” Battle said. “There were some really cool games we created.”

Woodward was the main setting where the boys of the neighborhood would collect, but during basketball season, Harrison Park was the venue. You couldn’t play if you couldn’t play.

“If you weren’t good, you couldn’t get in a game, and if you did, you had to win to stay,” Battle said.

When Battle wasn’t hunting a game, he spent a great deal of time on the campus of Birmingham-Southern College, a private, gated liberal arts school just off of Arkadelphia Road within a stone’s throw of Legion Field. Battle’s father was the athletic director and head of the physical education department at Birmingham-Southern, and made such an impact on the institution that a boxy coliseum resting on the current campus now bears his name.

Despite the elder Battle’s prestigious job title, Battle describes his family’s socioeconomic condition as “working class.”

“My mom and dad were both schoolteachers,” he said. “Most everybody’s dad and mom worked.”

In those days, sons worked, too. At twelve, Battle zigzagged through West End on a seven-day-a-week paper route, hurling copies of The Birmingham News onto neatly pared lawns. “I had a bicycle to deliver papers and then you had to collect and pay your bills every week. If you hadn’t collected enough, it came out of your pocket.”

This experience was beneficial for Battle two principal reasons: it helped him learn the value of the dollar and the importance of hard work.

As a teenager, Battle worked at Southeast Bolt & Screw for Dave Upton and Fletcher Yielding, men who had started their business after buying an old hardware store. Battle worked eight hours a day and six days a week, shoving a grand total of $48 cash in his pocket by week’s end. “The first week the bosses invited me to lunch down the street on 2nd Ave. at Nikki’s. It was a great meal but cost me about $2.75. I calculated that working almost three hours for lunch wasn’t good economics and found baloney sandwiches taken from home would work much better,” Battle remembers.

Faith was an important element of the Battle’s lives. Battle’s grandfather, a local Methodist minister, had a strong influence on his eight children, of which Battle’s father was the eldest. “I grew up in an environment where education, community, and faith were important,” Battle said. “I certainly believe in the power of God, the power of prayer, and the hereafter.”

These early influences built a foundation of faith in Battle that has undergirded him throughout his entire life.

Although his days at Woodward and Harrison Parks planted valuable athletic seeds that would later germinate, the activity on these fields did not produce a svelte-framed competitor. Battle admits when he went out for freshman football at West End, he was “short and fat” and “one of the two slowest guys on the team.” He also picked up a nickname—“Turtle”— and a successful day was avoiding coming in last in wind sprints.

Turtle would eventually emerge as an elite athlete, but he would first have to be challenged by his coach. “I told my coach, Cotton Roy, I wanted to go out for baseball, and he looked at me and said, ‘Son, you need to learn how to run’. So, he told me I was going to run the 440 on the track team. I thought it was the cruelest thing you could do to a kid.”

Instead of complaining, Battle started training. Over the next few months, his body underwent a metamorphosis, from short and fat to tall and skinny. Battle had so learned to run that by his senior year, he competed in the finals of the 440-yard dash in the state track meet.

“I came in last in the finals, but I ran my fastest time of the year,” he said. “One of my proudest moments in athletics was making it to the state finals as one of the top eight runners in the state.”

Lettering in three sports— basketball, football, and track—Battle became one of the state’s top athletes, blossoming under head football coach Sam Short and signing an eventual football scholarship with Alabama. To this day, Battle still holds fond memories of his coaches: “Coach Short….refereed basketball games well into his seventies. And coach Billy Mitchell was an assistant football coach and head basketball coach. Both had a positive influence on my life.”

Before Battle arrived on the Alabama campus, he was able to get an early notion of what his next year would look like. Bud Moore had been a teammate of Battle’s at West End and was a member of the Alabama team when Bryant returned in ‘58. Through this connection, Battle received an inside look into the program, as Moore intimated to his friend about his experiences.

“I would talk to Bud about what was going on,” Battle said.

Supplementing that understanding was a chance meeting with greatness. At a high school all-star game held in Tuscaloosa, Battle saw the sublime athlete hailing from a diminutive dot in the country: the pride of Excel, Alabama, Lee Roy Jordan.

Battle once described the event: “People were getting knocked down all over the field…and Lee Roy was doing most of the knocking.”

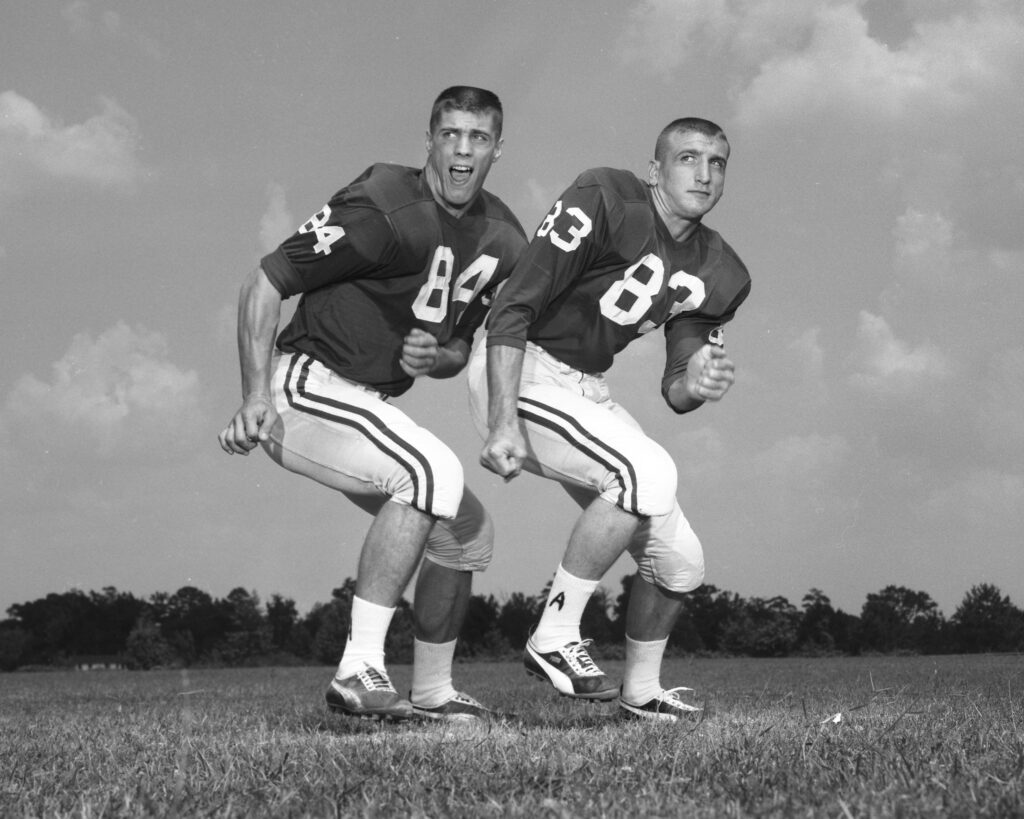

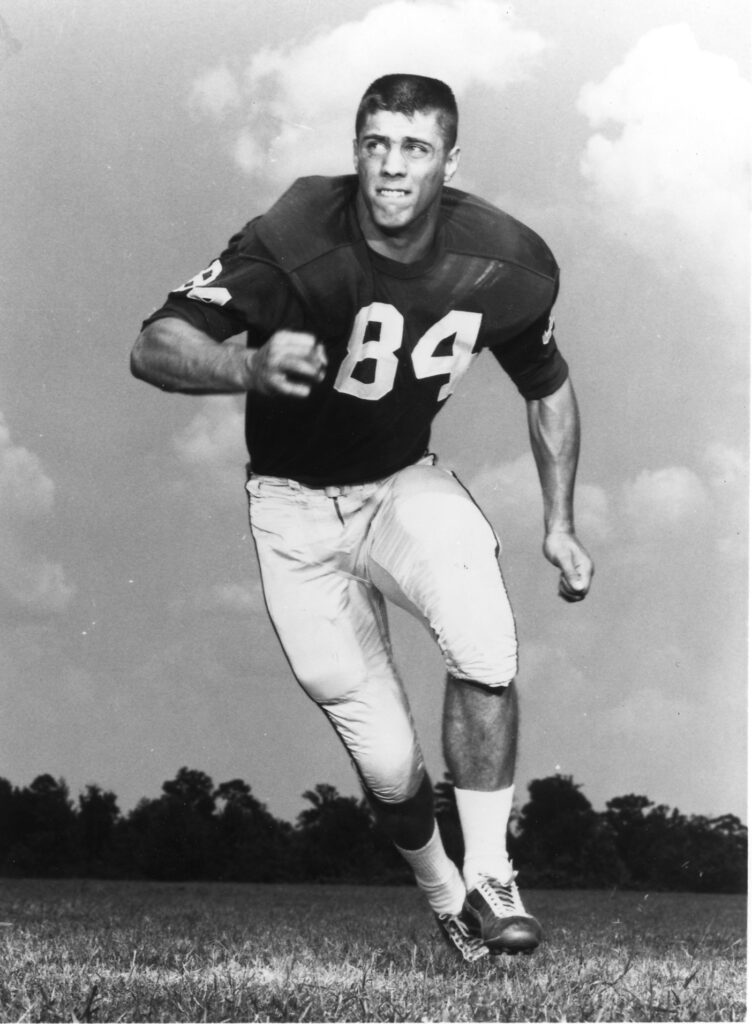

Contrasted to the strapping Jordan, who boasted over two hundred pounds of solid beef, Battle weighed 178 pounds when he signed at Alabama. Pimpled and sylphlike, Battle joined the Tide corps in 1959, and through a rigorous eating schedule, was able to pack on a few more pounds before reporting to campus.

“When I signed, Coach Bryant said, ‘Don’t gain any weight,’” Battle remembered. He reported at 190 and got up to 200. He was one of the larger players on the team.

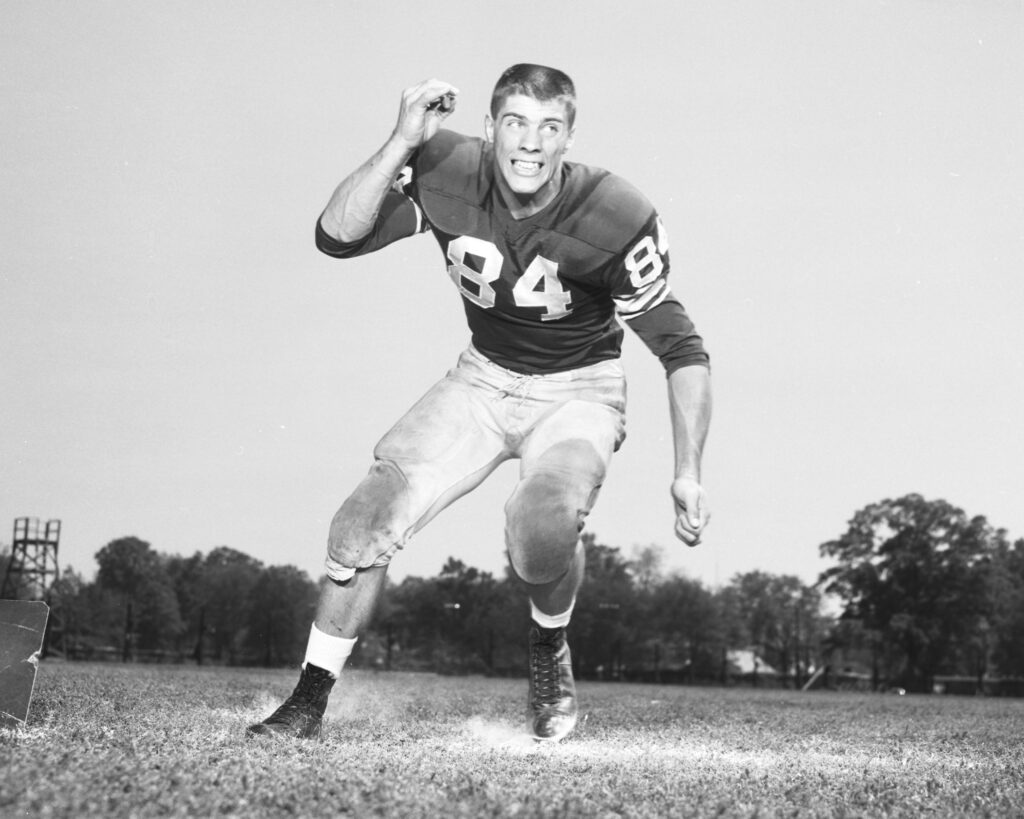

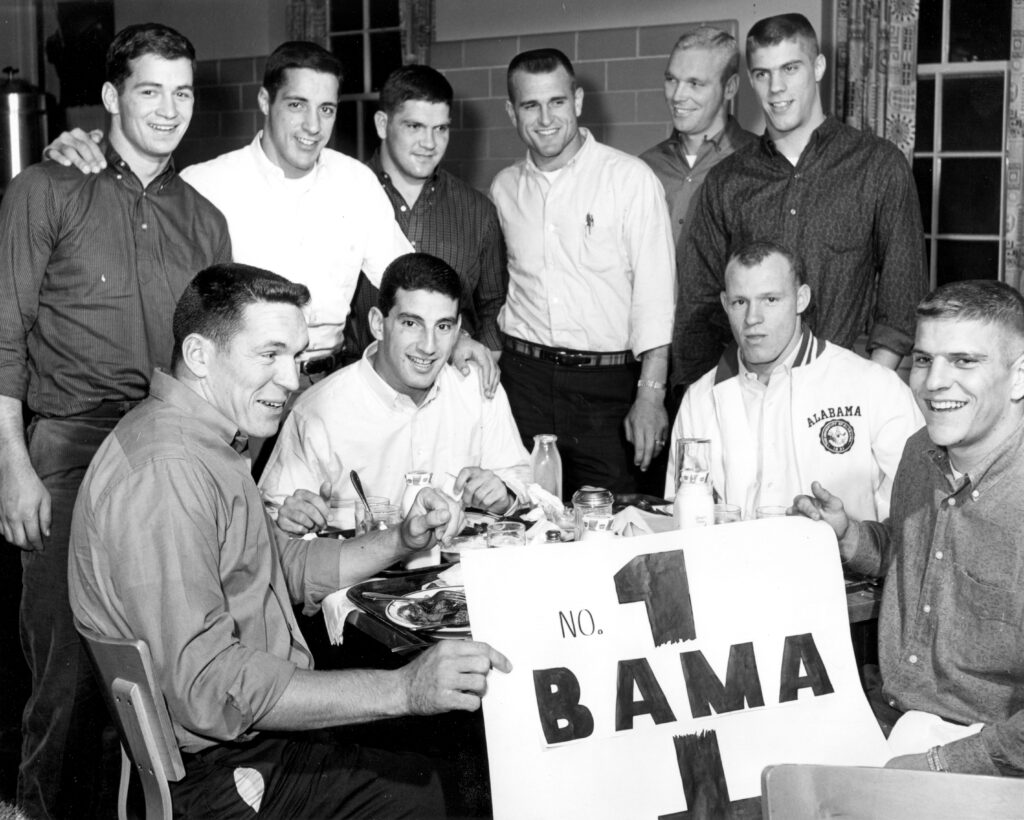

Battle lettered for three seasons at Alabama at end but never received the accolades of, say, Pat Trammell or Billy Neighbors. A quiet influence, Battle was content to play solid ball and shirk approbation for the greater benefit of the team. During his time as a player at Alabama, the Crimson Tide won the 1961 National Title—Bryant’s first as a head coach.

A.D.

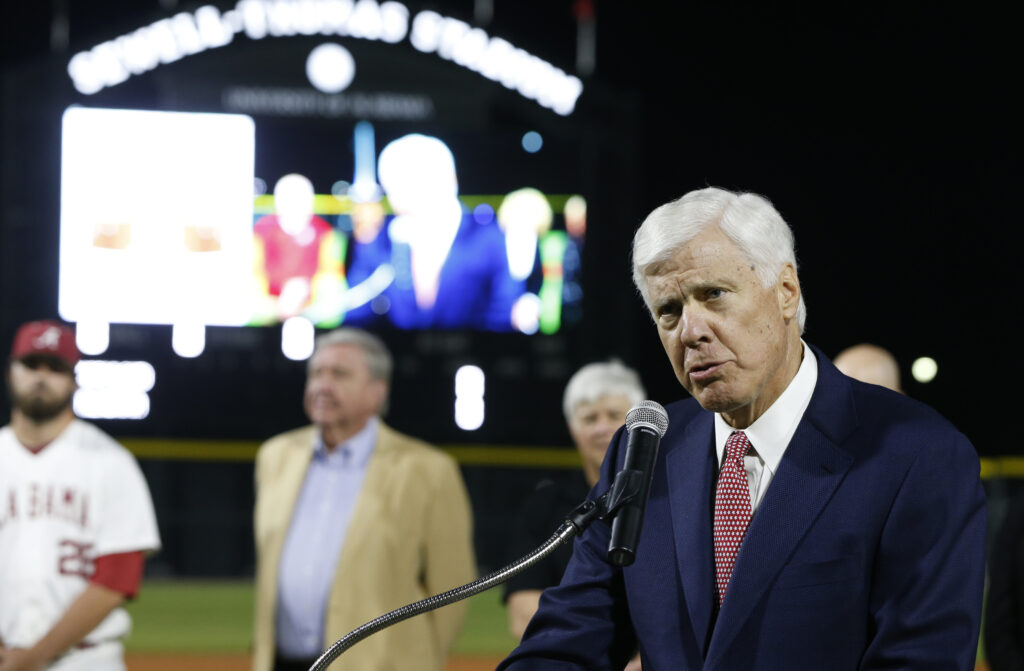

It was doubtful at that point that Battle believed life’s unanticipated turns would eventually lead him to the Athletic Director’s office at the University of Alabama, yet exactly a half century after leaving Alabama to accept a job at Oklahoma, Battle took command of the podium on March 22, 2013, when, as a white-haired man, he filled the role that his coach once so authoritatively held.

“If I didn’t do this, I’d regret this the rest of my life,” Battle said in his acceptance speech.

Three years later, Battle relaxed in a chair in his athletic director’s office in Tuscaloosa, one leg slung across the other at the knee, silk tie over a white, button collar shirt still heavily starched though it is afternoon, pensive, jovial, reflective, iron-jawed, at peace, satisfied. Besides a small hunch in his walk, he had aged perfectly—at least, in terms of outward appearance (many would say he became handsomer as he got older). His face Hollywood chic, his hair impeccably white.

But, as few realized at the time, the fine-looking façade betrayed a tumorous strife occurring within his body.

Bill Battle had cancer.

Only five months later, his appearance had drastically changed. His coveted coif has been sheared down, his fleshy skull prominent—the flagrant consequence of chemotherapy.

Battle initially chose not to go public with his condition—he had been keeping it semi-secret for over two years—and it was a shock to see him sans his ivory mop of hair.

Back in 2014, after a routine physical, doctors at St. Vincent’s hospital in Birmingham detected a tumor in Battle’s vertebrae. He was diagnosed with a plasma cytoma and underwent radiation, driving to UAB hospital in Birmingham every day for five weeks. In deciding to keep the matter private, Battle told only his close associates in the athletic department, who didn’t utter a peep. During radiation treatments, he never missed a day of work.

About a year went by and Battle’s blood work, done at the Manderson Cancer Clinic at DCH Hospital in Tuscaloosa, looked good. His wife, Mary, a former oncology nurse, had been in contact with the doctors, who told her Battle needed a PET scan. After a bit of convincing, Battle relented. Doctors found two spots of protein buildup, which could develop into lesions that might attach to bone. They suggested chemotherapy, an idea that Battle didn’t particularly like.

So, the Battles went to M.D. Anderson Hospital in Houston to explore options. There, the doctor concurred with the Birmingham physicians: he needed chemo. Battle also was told that when he reached remission from the chemo he should undergo a stem cell (bone marrow) transplant.

Battle decided to put the chemotherapy off until late summer so he and Mary could travel to Europe and a second home in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Finally, in mid-August of 2015, he began chemotherapy. He took two shots per week and pills every day. The cycle was four weeks: three weeks on and one week off. Battle went through three cycles and lost twenty pounds. Again, he never missed a day of work.

Though his body had grown frail, he continued in his duties as Athletic Director. When asked why he’d lost so much weight, Battle replied, “Well, I’ve been working out real hard.”

For the stem cell procedure, Battle heard of a doctor in Atlanta who was a “head knocker” in stem cell research and development, Dr. Sagar Lonial. Battle thought Atlanta was more convenient than Houston (since two of his children lived there), and decided to move forward with the doctor in Georgia. “I was OK harvesting the stem cells, as that is a pretty easy procedure, but I wasn’t sure that I wanted or needed to do the transplant, which can be a pretty serious procedure,” Battle said.

He and Mary went to Atlanta that February and harvested the stem cells, which are then frozen and stored for whenever the need arises. “The stem cell transplant procedure gives you one big dose of chemo and two days later, puts your stem cells back in. In about a week, the chemo takes effect, hopefully killing all the bad stuff in the marrow, but also killing a lot of good stuff too,” Battle said.

With all the new drugs coming to market, Battle hoped he could delay long enough for something to come along and solve the problem.

“I looked from February to June to find a doctor to tell me I didn’t need the transplant now. I couldn’t find anyone so I decided to go ahead and get it done last summer,” Battle said in 2016.

The month of June rolled around and Battle consented to the procedure. Since he would be in the hospital for two weeks and knew that his hair would fall out at the end of it, he finally went public with his condition, taking a leave of absence beginning on June 21.

“I am very comfortable with the diagnosis and treatment plan,” Battle said in a statement. “I am looking forward to getting this behind me and continuing my active lifestyle, as well as continuing to lead our athletics department. My experience has made it clear to me that cancer can be a treatable disease that can be dealt with while maintaining a high quality of life.”

On Saturday, June 25, Battle began the stem cell transplant procedure at Emory University Hospital. That day, he went in for three days of shots that prevented sores in his mouth and esophagus—“It makes you feel like your mouth is covered with Milk of Magnesia,” Battle described.

He also received a big dose of chemo, which he thought “was going to whack me.”

Doctors said that he would be fine for the first four or five days—things would be “boring,” they suggested—and after that, he would begin a three-day descent into the basement. At Day Eight or Nine, he’d be at the bottom.

“Day One, Two, Three, Four, and Five, there was no bad feeling and we walked every day,” Battle says. “Mary and I tried to walk outside but it was so hot that we walked around the unit. Twenty-one laps was a mile and we walked up to five miles a day.”

On Day Six, Battle started to lose energy, and as doctors predicted, on Day Eight, he was at the bottom. The same day, doctors discovered a staph infection from a trifusion, which was a cause for concern, and a PICC line was installed. He was also experiencing chills and sweats, had fever, and his white blood cell count was at zero.

Doctors began to pour in antibiotics and told him that they would not let him leave the hospital until they were confident that these problems had been resolved. Three days later, his white blood cell count was at 200 and climbing. By the next Saturday, it was at 2600.

“And they said, ‘You’re outta here by noon,’” Battle remembered.

The last day at the hospital, Battle woke up with tufts of hair in his face and mouth. He took a shower and his white locks fell out copiously.

The recovering patient spent the next ten days at the house of his son, Mike. Mary administered IVs and Battle sped up the process by allowing Mike’s wife, Mary Fleeta, to shear his head.

After ten hard days, the Battles left Mike and Mary’s home and traveled to their ranch in nearby Ellijay, Georgia. They returned to Tuscaloosa the following week—“I wanted everybody to see that I wasn’t’ dying”—and later spent two weeks at Jackson Hole, where he walked between five and eight miles per day.

Battle says that he was never not in contact with the athletic department, checking emails and phone, and was pleased with the progress his staff had made over the course of the summer. He physically returned to work on August 15.

Navigating this frightening experience with the same class and courage that he’s exhibited his entire life, Battle says that he embraced his new “do,” telling all of the baldheaded staffers to come take pictures. “We’re brothers,” he’d say. He admitted he even “enjoyed” his baldness, especially since he’s in and out of the shower in five minutes, and that losing his hair was not particularly humbling, just part of the process.

For Battle, the prognosis was about ten years, which he was planning on anyway. Post procedure, he had zero side effects of cancer, only complications from chemo. He felt good and strong. He went to work. He walked three miles or worked out on the elliptical machine regularly. He kept a great attitude.

“From the family that raised me to the family we raised, I’m proud of it all,” he says. “If it’s my time, it’s my time, but I’m going to fight it kicking and screaming. And if I go sooner rather than later, that’s okay because I’ve lived a great life,’ he said.

Finale

Bill Battle knows he didn’t architect the second wave of Alabama football, but it’s safe to say he was, at the very least, one of the brick masons. Like an owner of a terrific house, Battle desired to pass the structure onto the next person in better shape than he found it. And that he did.

Battle oversaw tremendous facilities upgrades at UA, including the $42 million rebuilding Sewell-Thomas Stadium into one of the finest parks for college baseball in the country. Athletic revenues have continued skyward, championships were won, and five coaches were hired, including former San Antonio Spurs player and Dallas Mavericks head coach Avery Johnson.

Committed to building champions both on and off the field, Battle helped to further staff the academic side of Alabama athletic department and under his leadership, a career leadership and development center in the Bill Battle Academic Center was started.

“We do a great job of educating and graduating our players, but we needed to do a better job of preparing our graduates to get jobs and to follow them throughout their career,” said Battle. “Our First and Ten Club are leaders in the community that come in and help our players better understand different job opportunities. They also participate in job fairs throughout the year and try to help our players locate jobs. Our A-Club is a network of former letter winners scattered all across the nation and many parts of the world. We are working hard to get them all connected through the internet if not coming back to campus. If we can, we can create a powerful network that can make a difference in a lot of people’s lives.”

When asked about his legacy, Battle says, “somebody else’ll have to answer that.” Though he’s content on leaving his mark to the pundits, he does reveal how he’d like to be remembered.

“I hope they remember that (I) loved the University of Alabama and every decision (I) made was what (I) believed to be in the best long-term interest of the University,” he says.

Overall, Battle recognized his duty as a steward of the Alabama athletic program. After all, good stewardship requires a degree of humility, since the very definition of a steward is someone who believes in something greater than himself. To that end, Battle was content to shovel the program into the gut of the next athletic director without credit or fanfare. Alabama football is bigger than any one man, and he was satisfied that he played a role in the perpetuation of Crimson Tide athletics.

The mission of the athletic department, as he saw it, was “to recruit and develop student athletes to compete at the highest levels in intercollegiate athletics; to educate and prepare them to compete at the highest levels in life after graduation; and to do both with honor and integrity.”

“That is what I have tried to live and have tried to get our coaches, administrators, and student athletes to believe in and live,” said Battle.

Odd as it may seem, Battle, with all the accomplishments and accolades under his belt, didn’t get as much recognition as perhaps he deserved. He was not a famous person outside of the Alabama football family, yet his contribution to collegiate life cannot be overstated.

His was a story that canoed its way through the rapids of life, and though it may have seemed as if he was floating along because his success and perseverance seemed so effortless, Battle excelled in all phases of his life because he always subscribed to the idea that if you just do your job and keep your mouth shut, good things will happen. Battle happily shunned the tickertape life, one that pedestals self and seeks incessantly the good-feeling of applause and commendation, for a life of hard work, sacrifice, and humility.

Battle founded the most successful business in the history of college athletics, grew it to a multimillion-dollar enterprise, and in the end sold it for millions more. He was a three-year starter as a player and a very good coach, though perhaps things didn’t end exactly the way he would have liked. Battle was happily marred to his wife, Mary, and once said, “she lights up my life every day.” Together, Bill and Mary had four children and seven grandchildren.

Since that moment, so long ago, when Bill Battle stepped down from the job at Tennessee, it is safe to say that he collected himself and became even more successful than being the head man in Knoxville. He soared once again to the top of his profession, completely reinventing himself within the framework of athletics, one of the many loves of his life.

Rare is it that one finds success in one field; Battle found success twice. And though the end of one field of study arrived sooner than anticipated, that crucible ushered in perhaps the finest years of his life, save for those four years as a player at Alabama. Such that at the end of Bill Battle’s time, a new headline must be written:

In like a lion, out like a lion. TG

Cover photo courtesy UA Athletics