The 2017 documentary Mr. Chibbs shares a warts-and-all view of former NBA player Kenny Anderson’s off-court life. That chapter of an ongoing story ends with Anderson seeking to give back to the game he loves and conquer the temptations of an idle mind by landing his first collegiate coaching job. The open-ended film finally got its happy ending on September 10 when the Nashville-based Fisk University Bulldogs announced Anderson as its new head coach.

With all due respect to Fisk, a historically black college and university made famous in the 1870s by the still-active Fisk Jubilee Singers, its National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) status and scholarship limitations make it hard to compete for players with Vanderbilt or nearby mid-major powerhouses Belmont, Lipscomb, and Middle Tennessee State. Yet if any rookie head coach can galvanize a small school’s alumni, parents, and players in a big way, it’s the 14-year pro invested in becoming a life-tested mentor.

As chronicled in the film, Anderson’s experiences coaching at a Florida high school and for a youth travel league sparked his interest in molding college athletes. “I wanted to mentor and coach kids at the college level,” he says. “It didn’t matter if it was Division II, Division III, NAIA. I wanted to pay it forward and impact someone’s life.”

Anderson followed the advice of new Clark Atlanta coach and fellow pro basketball retiree George Lynch and applied for the Fisk job, replacing prior head coach Larry Glover, who became the university’s athletics director. “Glover coached here for a long time, and he did a good job,” Anderson says. “We’ve got some good players for this level. We’ve got some talent. We’ve got a good team for this level, and I think we can do some damage.”

Beyond inheriting the services of junior shooting guard Marcus Summerville and sophomore point guard Tyran Davis, Anderson joins a growing program that now has full university support and its first full-time athletic trainer. “We’re trying to build something here,” he adds. “The few presidents before didn’t really care about sports, but Kevin Rome, the new president, cares about sports.”

For future players, Anderson gets to sell a historically relevant and architecturally gorgeous university attended by around 700 students. For athletes most comfortable with small classroom sizes, it can provide a coveted chance to play college basketball and suit individual learning needs. They can get to know on a personal level not just their coach, but also their professors and academic advisors.

“Small is good for some kids,” Anderson adds. “It’s needed for some kids. Some kids go to bigger schools and don’t know what’s going on or how to survive.”

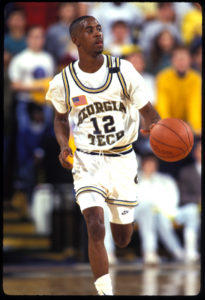

Few high school players in the 1980s earned quite as much attention as Anderson, the New York native and point guard prodigy who became the first four-time Parade All-American since the future Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Lew Alcindor. At Archbishop Molloy High School in Queens, he learned the value of coaches and mentors while playing for the legendary Jack Curran.

“I knew no freshman ever started for Coach Curran,” said former Georgia Tech coach Bobby Cremins in a 2017 interview with the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “I said, ‘Coach, if he’s going to start for you, I’d like to meet him.’ And I met Kenny Anderson and recruited him from that day on for four years.”

The hottest recruit in the same high school graduating class as Shaquille O’Neal could’ve gone to college anywhere, but his mother encouraged him to pick Georgia Tech over home state favorite Syracuse. Under Cremins, Anderson, Dennis Scott, and Brian Oliver comprised the “Lethal Weapon 3” team that reached the 1990 Final Four.

Had Cremins not pulled Anderson out of the game with foul trouble against eventual national champion UNLV, the three-headed basketball monster’s legacy might loom larger beyond metro Atlanta. As it is, Tech fans get to speculate on how a seven-point halftime lead could’ve been preserved, while Duke fans would rather forget their team’s 30-point loss in the finals to Larry Johnson’s Runnin’ Rebels.

Players arrive at schools like Fisk without such accolades or distractions. Instead of leaving after a year or two for the NBA draft, they come for four years of locker-room camaraderie and a chance to study and network their way to a full-time career. Chances to prove Division I and II recruiters wrong come in conjunction with the opportunity to score a private college education. Under these circumstances, Anderson prepares young men as much for life beyond basketball as he positions them to play well on the court.

“I’ve got a bunch of good kids,” Anderson says. “They want to work, and they work hard. I just want them to get closer to each other. Like I always tell them, always ask yourself how you can be a better teammate. I’m not talking about how you can score 15, 20 points a game. No, how can you be a better teammate? How can you pick that dude up when he’s struggling? Are you diving on loose balls, giving your body for the team? You might want to play, but someone ahead of you is doing well. Cheer for your teammate.”

A former head coach of the Continental Basketball Association’s Atlanta Krunk, Anderson knows he’s molding impressionable teenagers into well-rounded adults, not fine-tuning pro prospects.

“No one’s going to make the NBA here,” he says. “Let’s be real. It’s about being a student-athlete, getting a good job after you play or maybe going overseas to play. You’ve got to be realistic about your goals. I don’t know the percentages, but I played in the NBA for 14 years, and Scottie Pippen went to a small school. Dennis Rodman went to a community college and made it. It can happen, but you have to have a lot of drive and a lot of luck where somebody sees you and believes in you.”

Recruits idolizing LeBron and Steph, not Michael and Scottie, probably don’t recognize Anderson’s name at first. Fortunately, they’re a Google search away from learning why that hungry young coach visiting from Nashville carries himself like a star.

Anderson left Georgia Tech after his sophomore year as a sure-fire Top 5 draft pick. The New Jersey Nets selected him second overall, bringing him close to home for some of his most successful years in the league. After his 1991-96 run in Jersey, Anderson spent time with the Charlotte and New Orleans Hornets, Portland Trail Blazers, Boston Celtics, Seattle SuperSonics, Indiana Pacers, Atlanta Hawks, and Los Angeles Clippers. Even if he wasn’t a perennial all-star, Anderson maintained a solid career during arguably the most talent-rich era in NBA history.

On the surface, there’s an apparent disconnect between Anderson and his players. His recruitment and post-college aspirations were very different from those of the typical NAIA athlete. Yet what he offers beyond his impressive on-court résumé involves the less glamorous side of the former pro star’s sometimes turbulent life.

A rough upbringing by a single mother preceded his days as a high-school phenom. As an adult living in the public eye, stumbling blocks included the financial mismanagement that plagues many pro athletes and a 2013 DUI arrest that cost him a high-school coaching job. At age 48, Anderson has lived through enough tough lessons to serve as a stern warning and a credible mentor for his eight biological children and the student-athletes under his watch.

“I try to embed in those guys to have self-discipline, not just on the basketball court but in the classroom,” Anderson says. “They know I’ve been through a lot, so I think their antennas are up.”

Anderson’s first two games came Oct. 26-27 during the Fisk Jubilee Classic. His team soared in his debut, toppling Mississippi-based Rust College, 72-56. That confidence builder preceded a teaching opportunity—a 75-65 loss to Cumberland during which Fisk committed 20 turnovers. On Oct. 30, Fisk fell to visiting Morehouse 63-46 after losing the points-in-the-paint battle 28-10. Struggles continued in a high-scoring loss on the road to Tennessee Wesleyan, 103-74.

“We’re playing very hard but just not playing smart,” Anderson says. “It’s going to take some time. As a first-year coach, I’m trying to get my points across and my sets offensively together. We’re not catching it real good right now, but I think in time and with more practices, we’ll get it. They’re working hard and trying, but a lot of the stuff we’re dealing with comes from just bad habits we’ve got to break.”

With a 1-3 career record so far, Anderson has ample opportunities to prepare his players for more than a successful 2018-19 campaign. Regardless of its final record, this team can set the tone for a coaching career and a university invested in improving its athletics program.

“If I leave here and I leave it two or three times better than it was,” he said, “I did my job.”

Regardless of where the current, feel-good chapter of the once-turbulent Mr. Chibbs story may lead, Anderson is focused on his present opportunity– to help young men starved to play basketball beyond the high school level.

But most importantly, to help them build a life. H&A

Follow Hall & Arena on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram @talegatesports